Click on each image for more information.

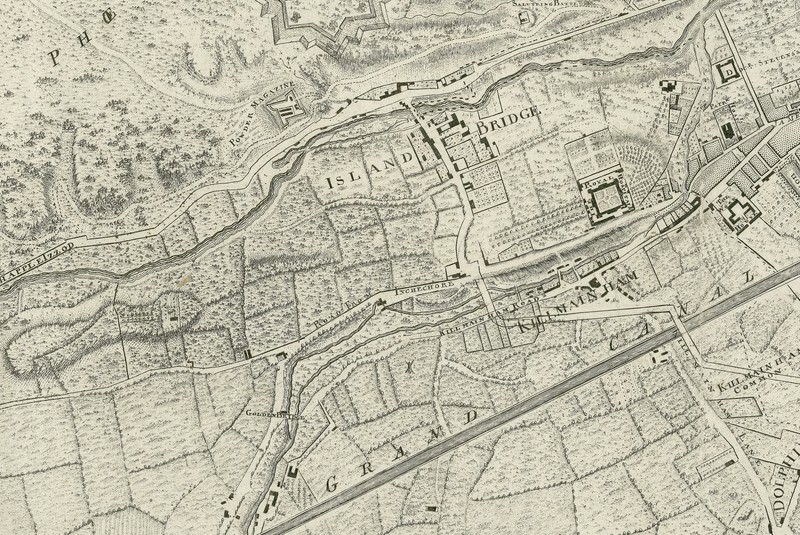

Map of Inchicore before Richmond Barracks was built. John Rocque map of 1775.

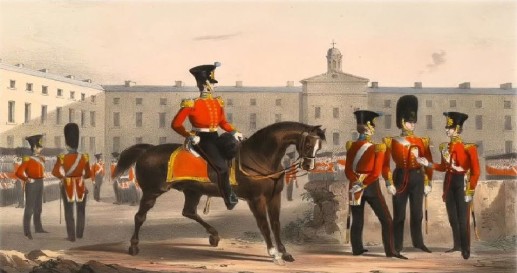

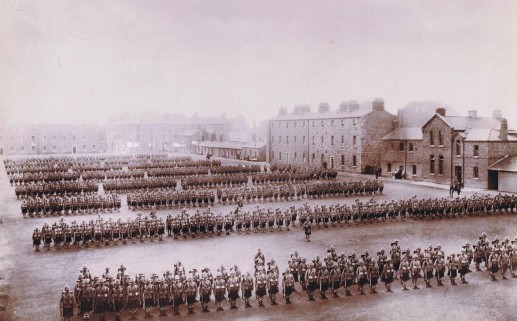

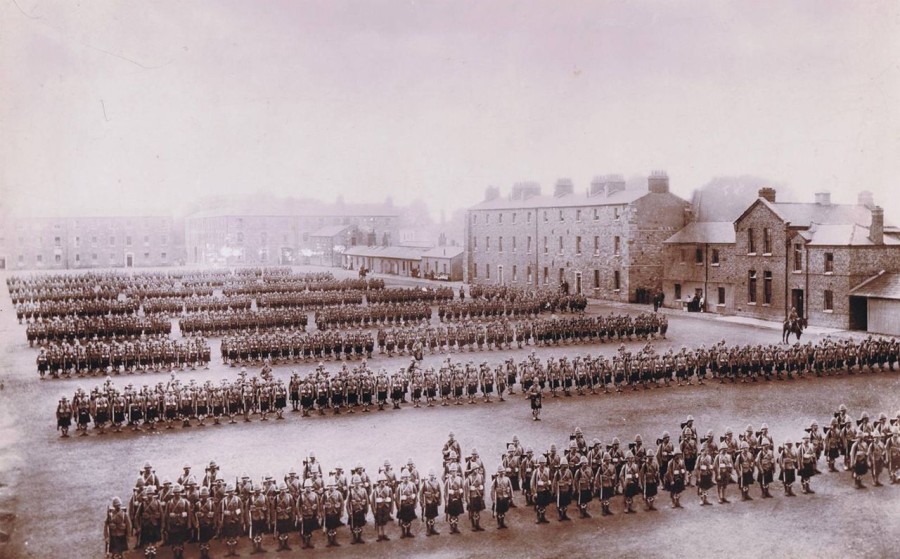

View of Richmond Barracks from the 1800s.

Inchicore village around the early 1800s. Richmond Barracks can be seen in the top right corner.

Richmond Barracks was built for the British Army, because during that time Ireland was under British rule.

Richmond Barracks and the Grand Canal around 1820.

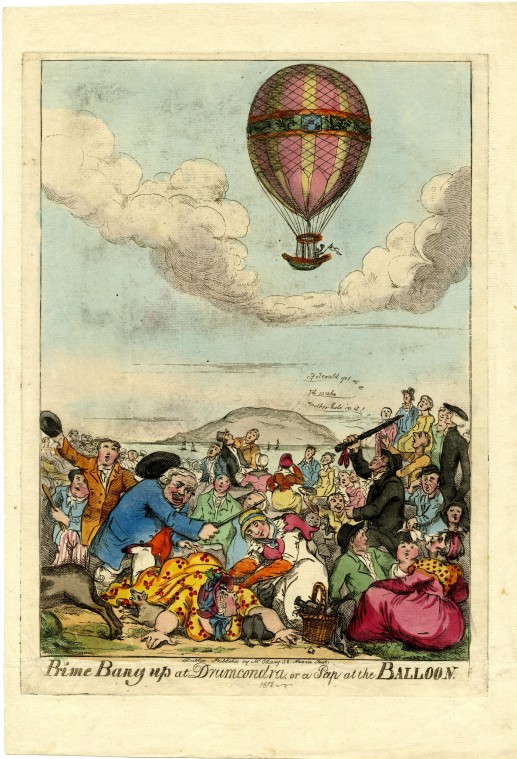

In 1816, excitement arises at Richmond Barracks.

The Dublin Weekly Register reports that in Richmond Barracks there are ‘discontents in the soldiery’.

The Whiteboys, who have already burnt police barracks in Cork, are thought to be about to attack Richmond Barracks.

The Oxfordshire Regiment from Richmond Barracks help fight a fire at Hibernian Woolen Mills in nearby Kilmainham.

Daniel O’Connell, ‘The Liberator’ and advocate for Catholic rights, opens Goldenbridge Cemetery, with the Catholic Association.

The consecration ceremony of Goldenbridge Cemetery was widely reported.

Incidents of public disturbance are reported, involving the soldiers and local people.

Within a couple of years, a temporary Chapel is built in Goldenbridge cemetery.

The 1840s is a decade of unrest with the Young Ireland movement pushing for independence from Britain.

The Commander of the Forces issues orders for all men to remain in barracks in Dublin so that they may be called on to deal with food riots and rebel attacks.

The potato crop fails several times all over Ireland, coupled with an inadequate policy response from the British government.

Newspapers begin to report on the Famine in Ireland as it grows steadily worse.

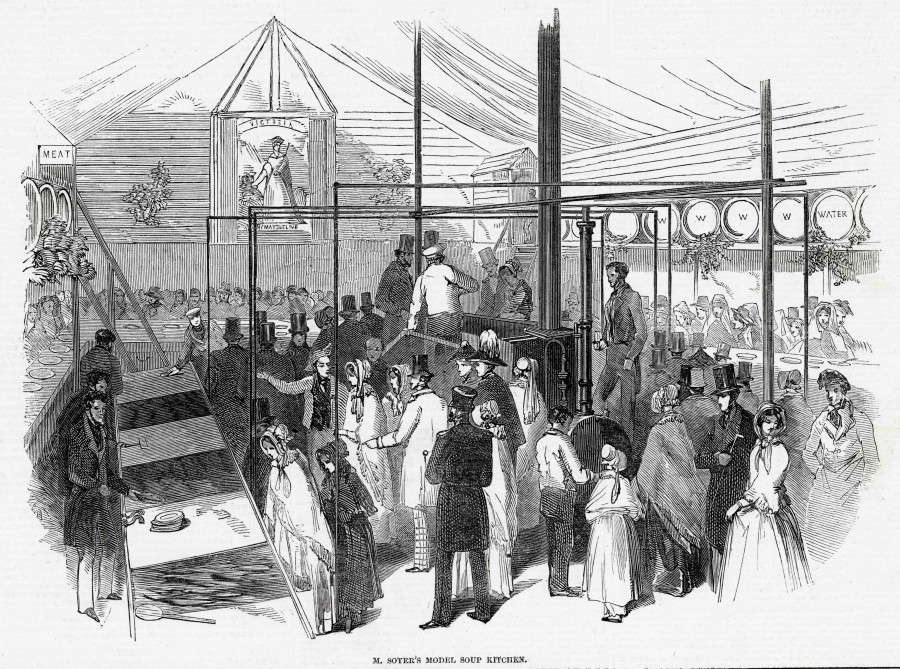

With government backing, the celebrity chef, Alexis Soyer, sets up a soup kitchen in front of the Royal Barracks.

The Great Southern and Western Railway line opens in Inchicore.

Dublin sees a severe outbreak of cholera and instructions are issued to the soldiers of Richmond Barracks.

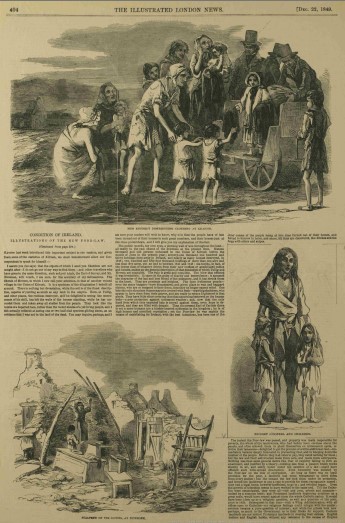

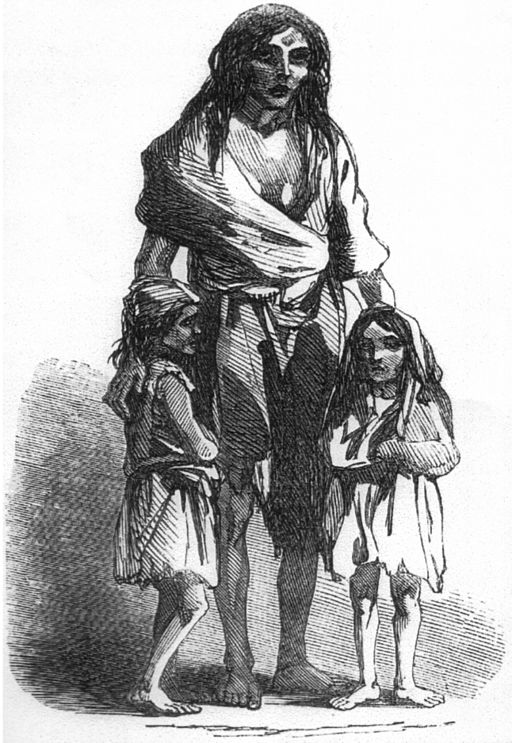

The sketch of Bridget O’Donnell and her two children is one that is often used to represent the Great Famine.

After six years of famine the population of Ireland has gone from 8.175 million (Census 1841) to 6.55 million (Census 1851) due to emigration, disease and death.

The Crimean War begins in 1853 and regiments of Richmond Barracks prepare to travel to the front line.

A report released on military living conditions gives an insight into the lives of soldiers' wives.

In another report the laundry facilities are listed and what is provided for children.

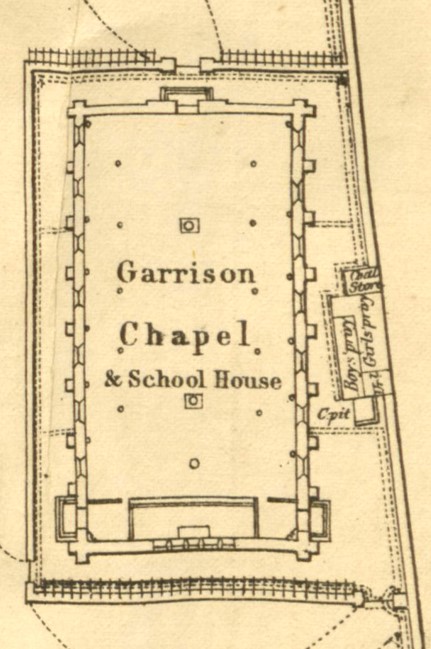

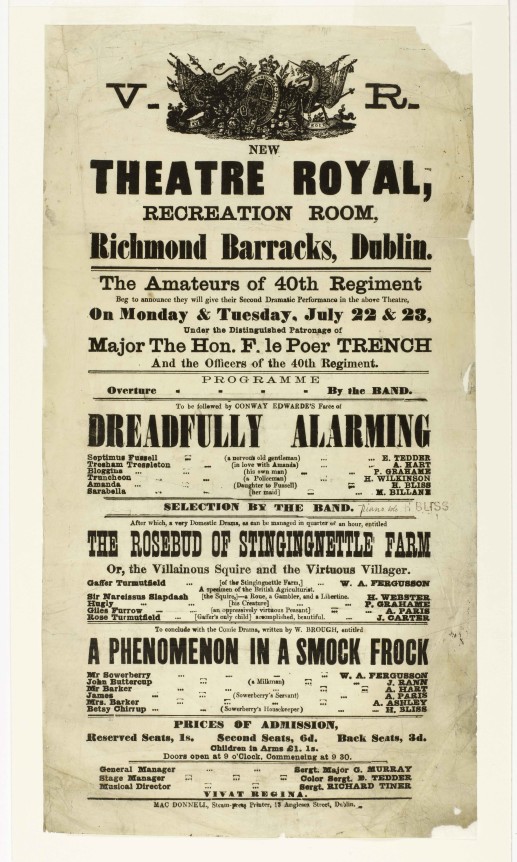

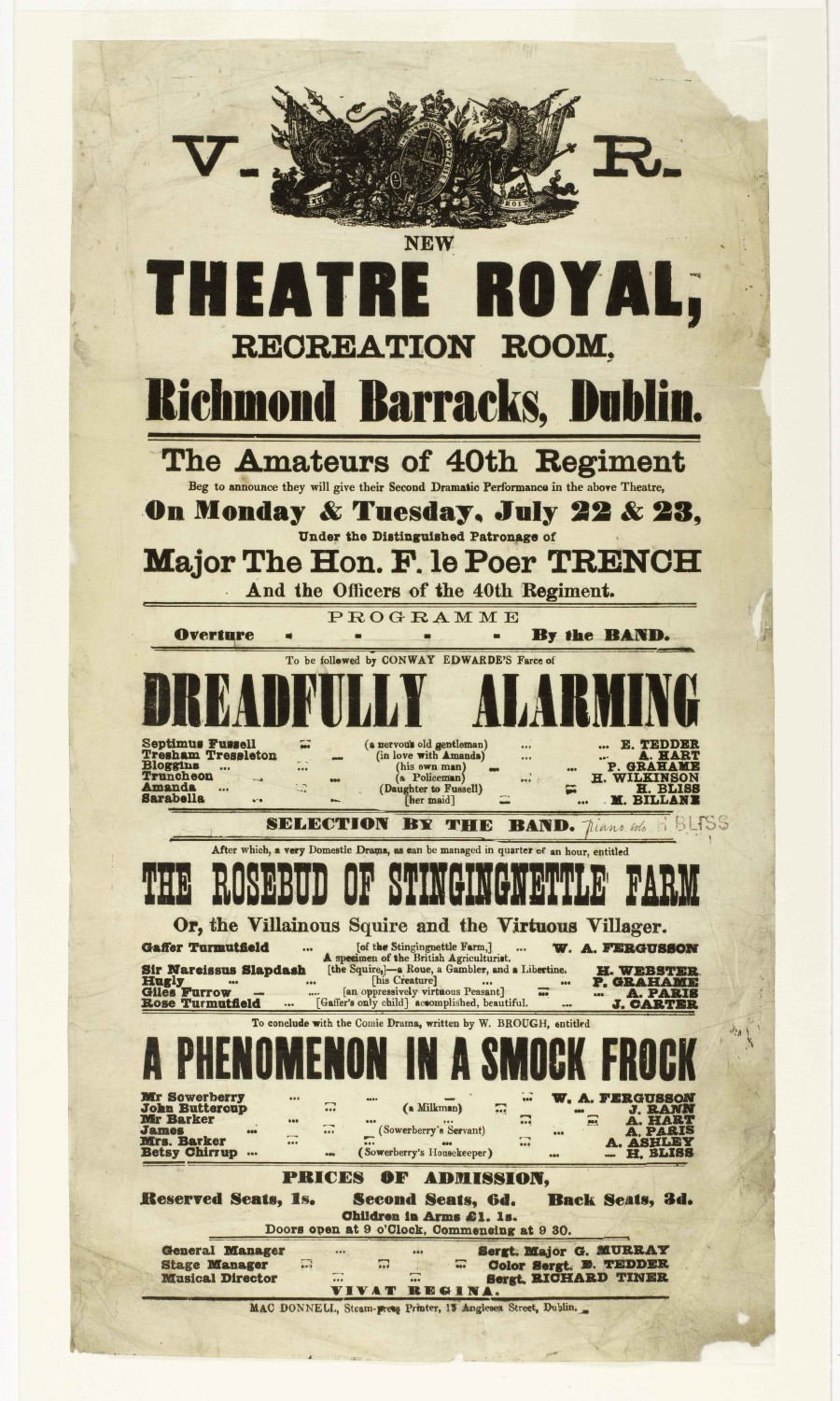

Recreation rooms are opened in Richmond Barracks, including a library and games room with plays and lectures taking place.

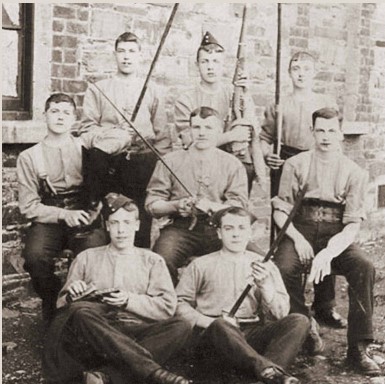

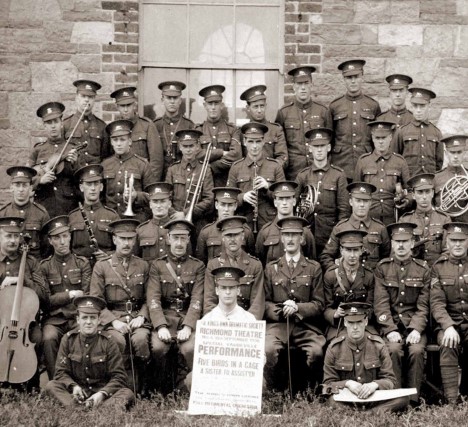

Amateur theatrics in military barracks were open to the public and provided opportunities for lower army ranks to socialise with local populations.

The War Office attempts to close Goldenbridge Cemetery, citing health and safety.

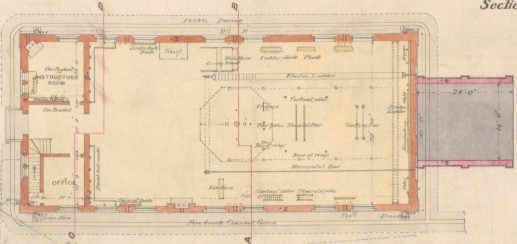

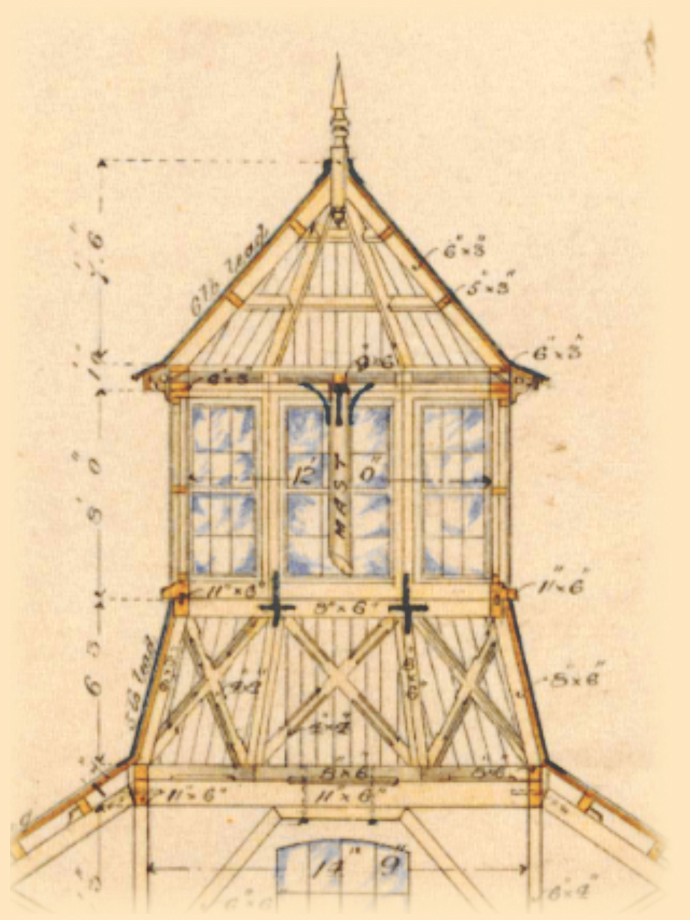

Depression and suicides among soldiers motivates the army into refurbishing the barracks.

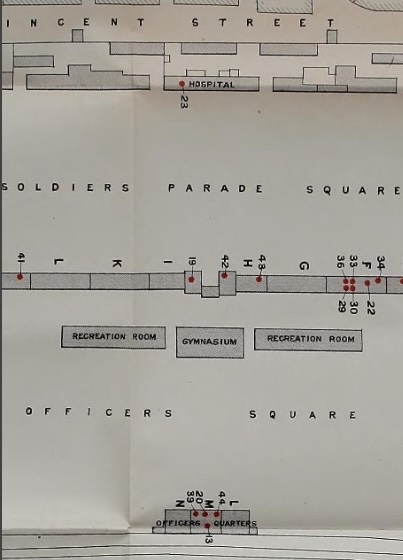

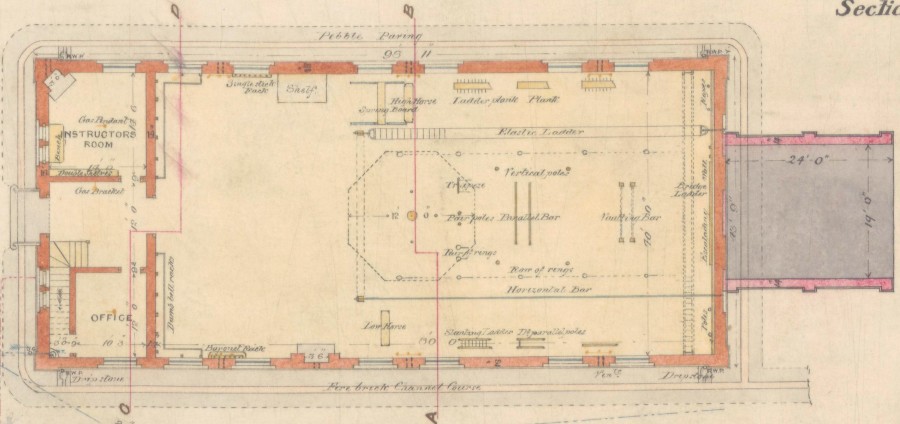

Plan of the gym in New Barracks in Limerick.

Due to an outbreak of typhoid or ‘enteric fever’ the War Office writes a report on the sanitary conditions in Richmond Barracks.

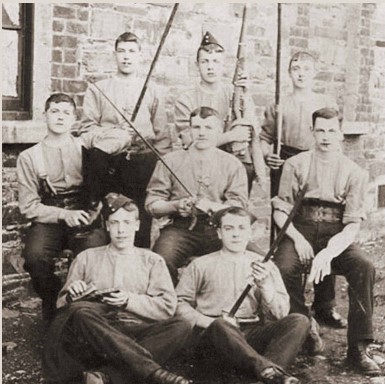

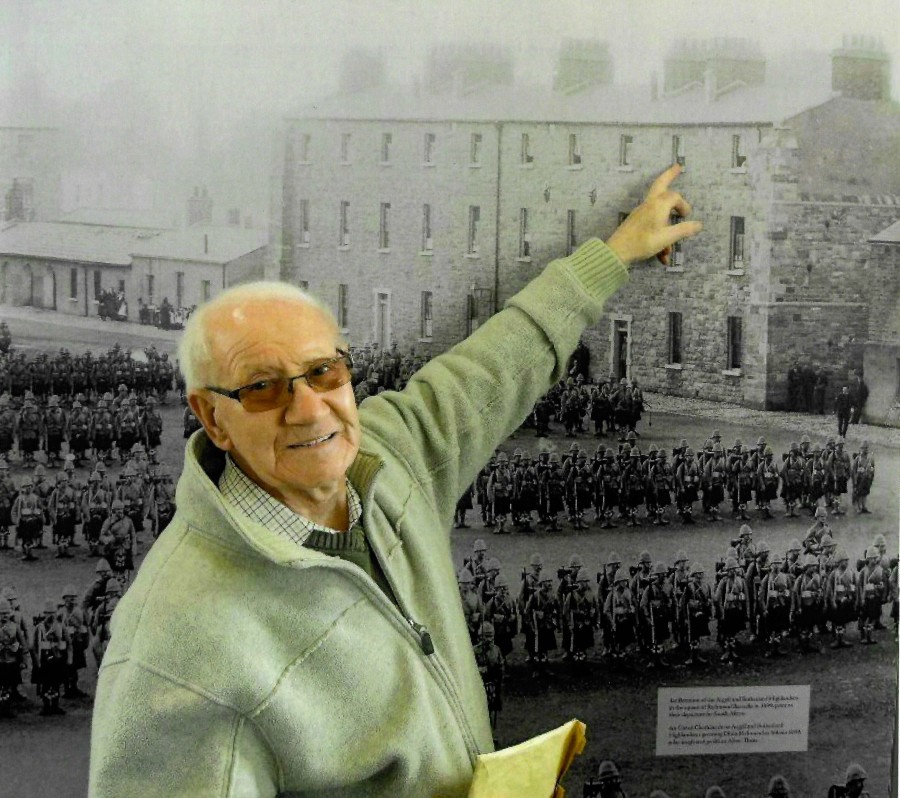

The second Boer war starts in South Africa and becomes Britain’s biggest conflict since the Crimean war.

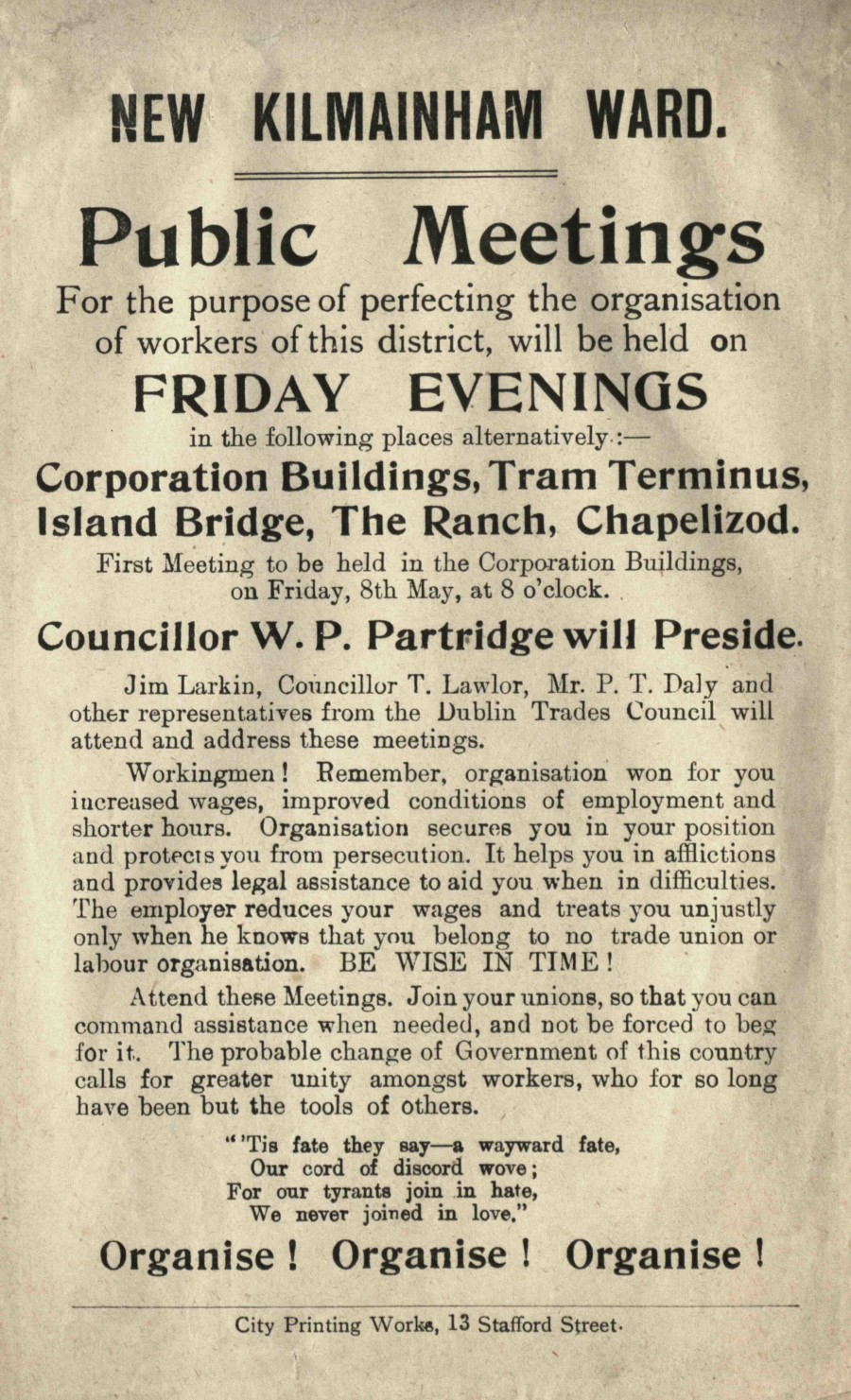

The 1913 Lockout is a city-wide industrial dispute resulting from Dublin employers locking out thousands of members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

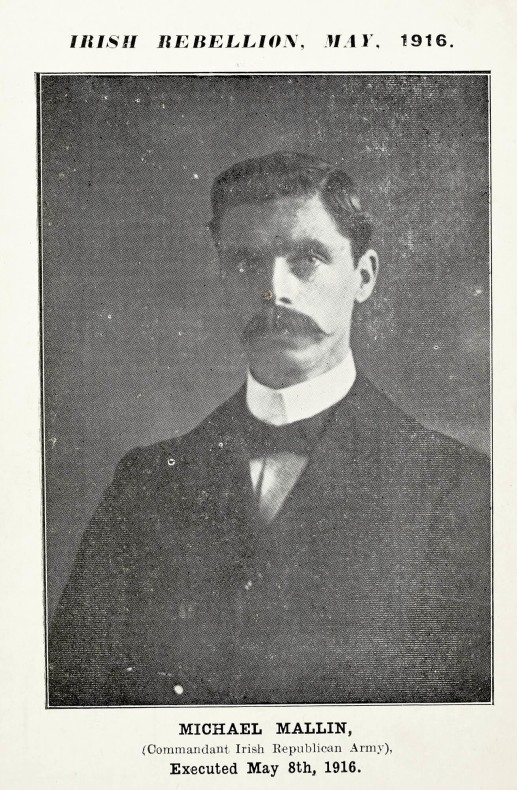

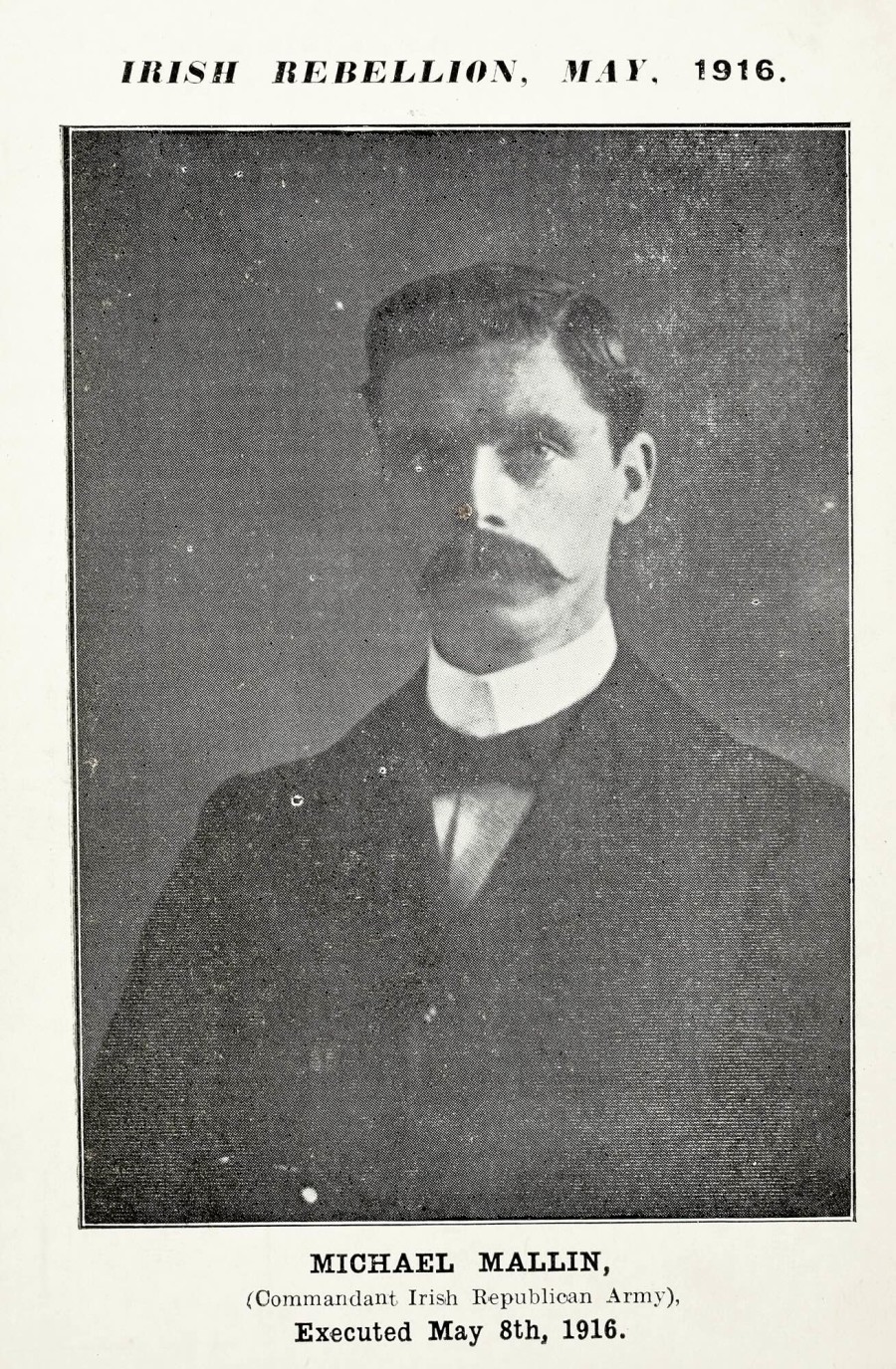

Emmet Hall at 122 Emmet Road was home to Michael Mallin, strike leader and Commandant of the Irish Citizen Army.

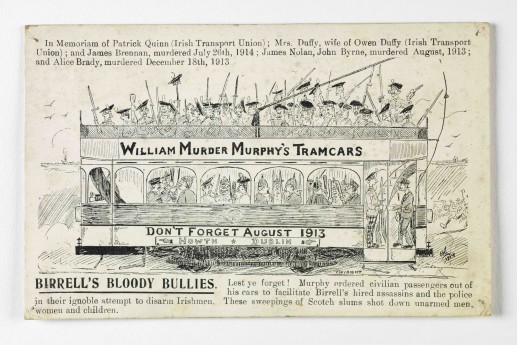

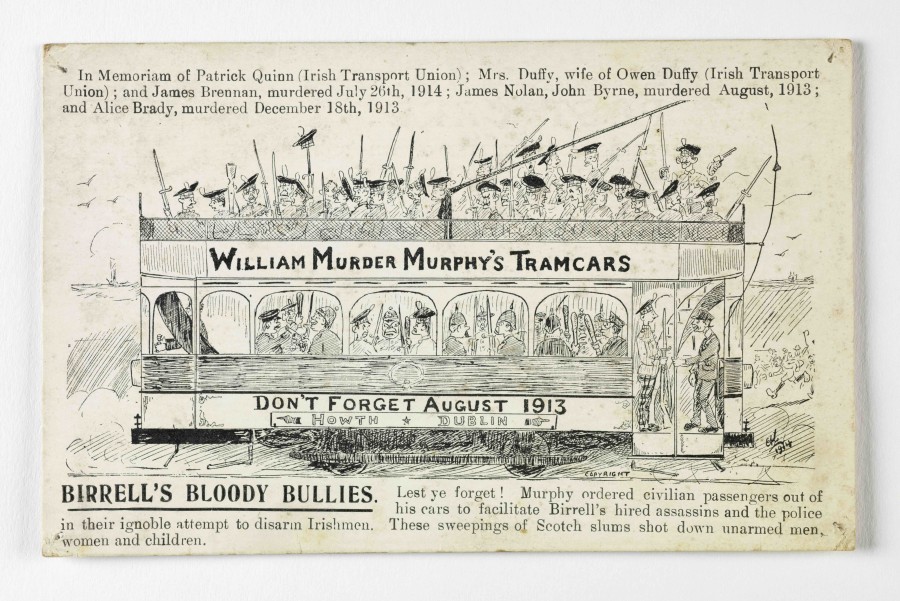

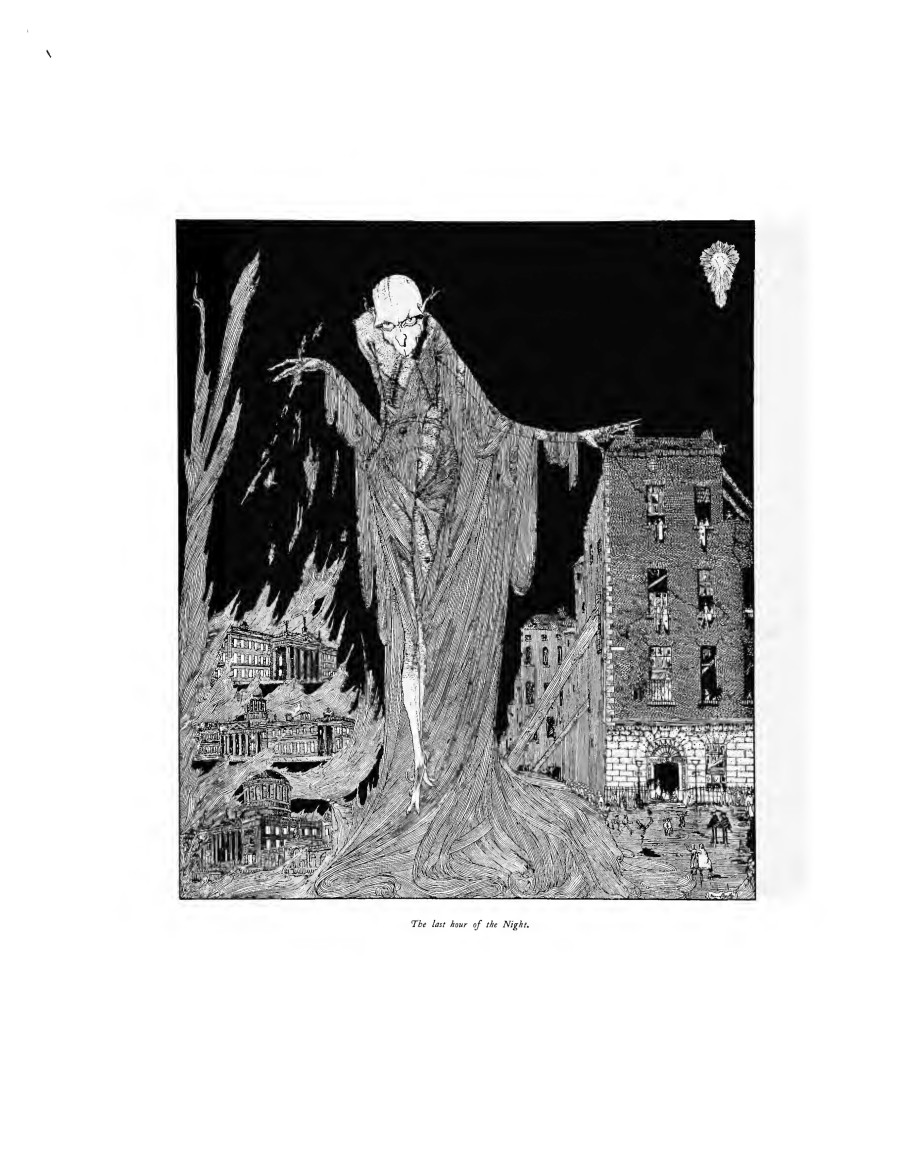

This cartoon references the tramcar used to bring the military to the Howth gun-running landing in 1914.

War is declared and troops are sent from Britain to the many barracks in Dublin to prepare them for the Western Front.

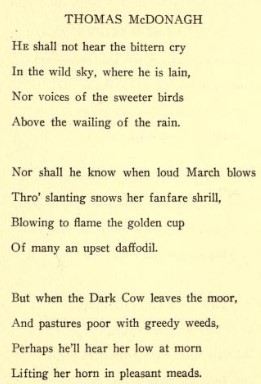

The poet Francis Ledwidge joins the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and is one amongst many young Irishmen who serve at Richmond Barracks.

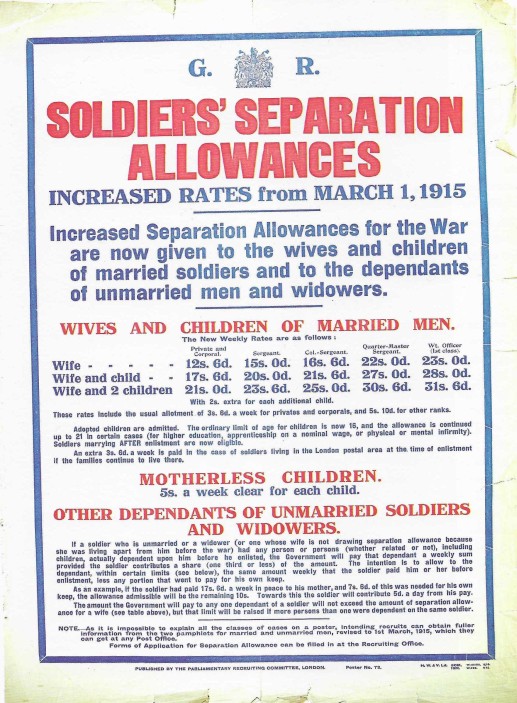

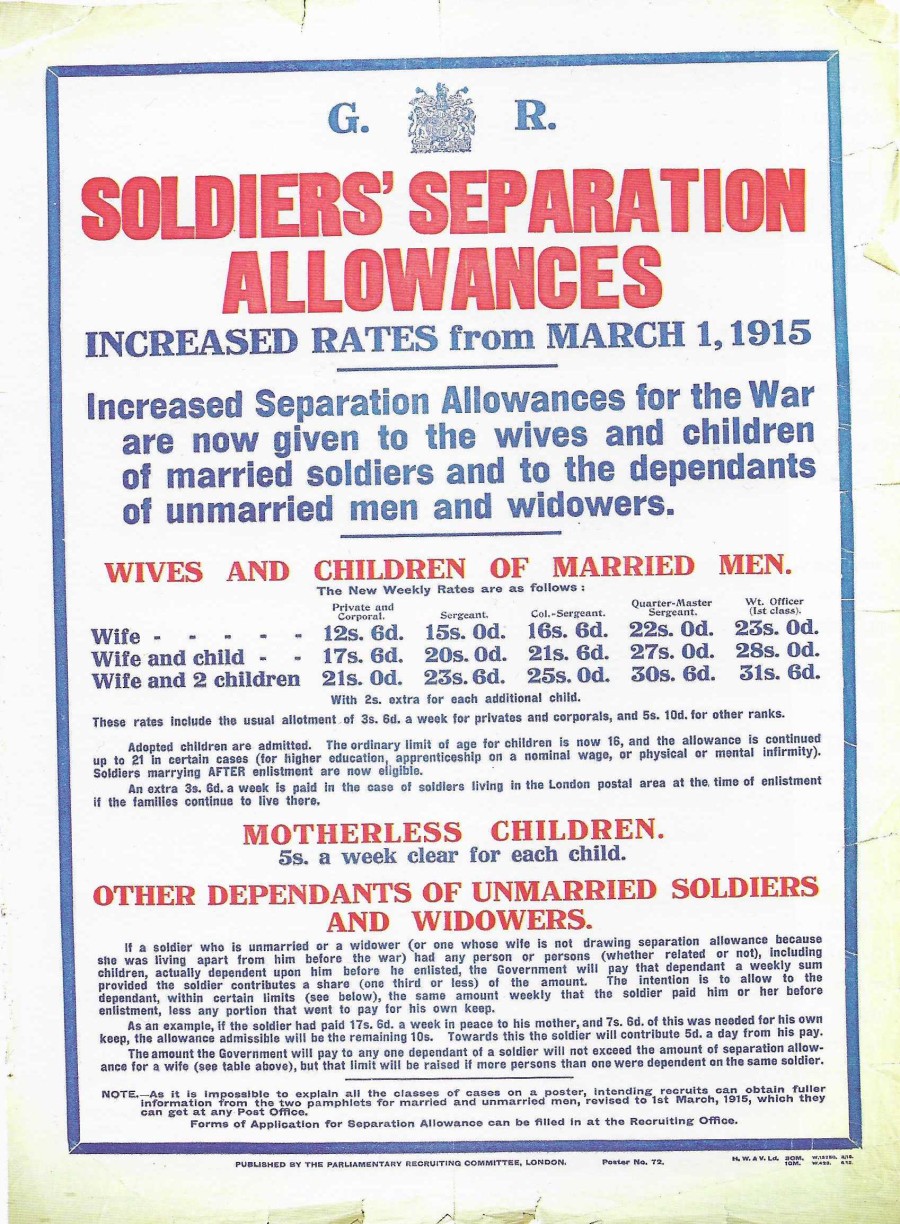

Wives of Irish soldiers in the British Army receive a ‘separation allowance’ and are popularly known as ‘separation women’.

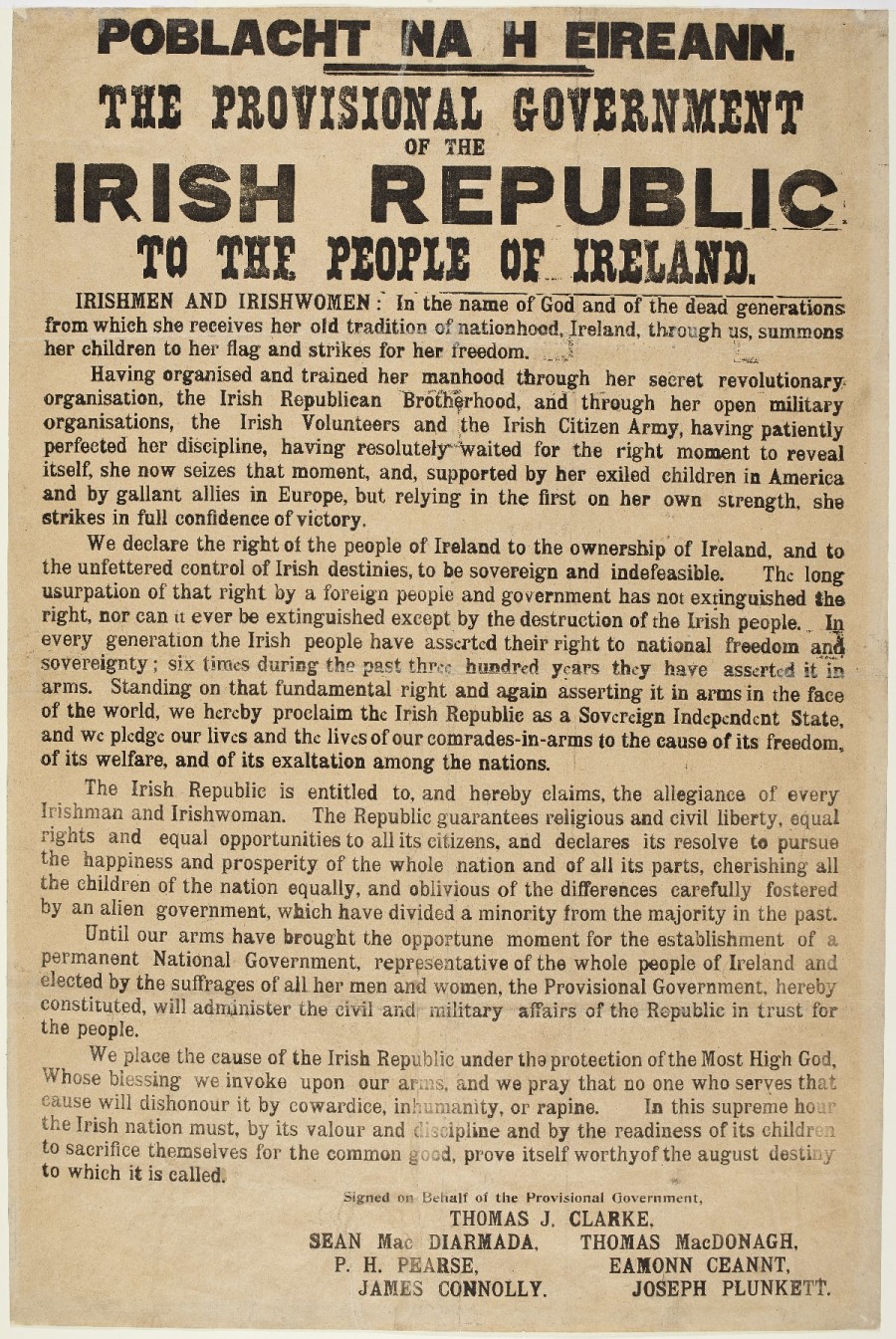

Support for Irish independence from Britain has been growing.

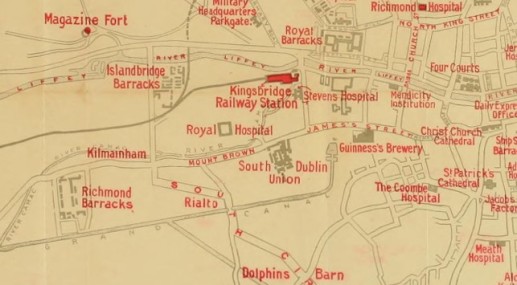

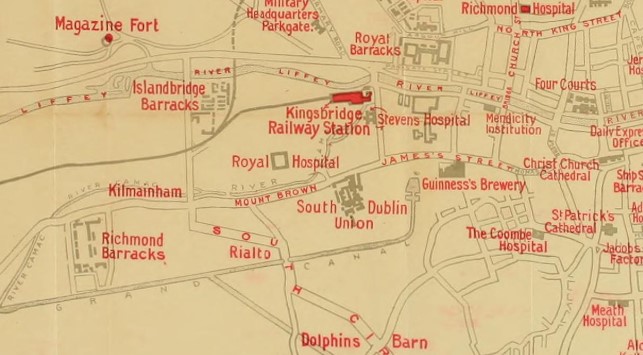

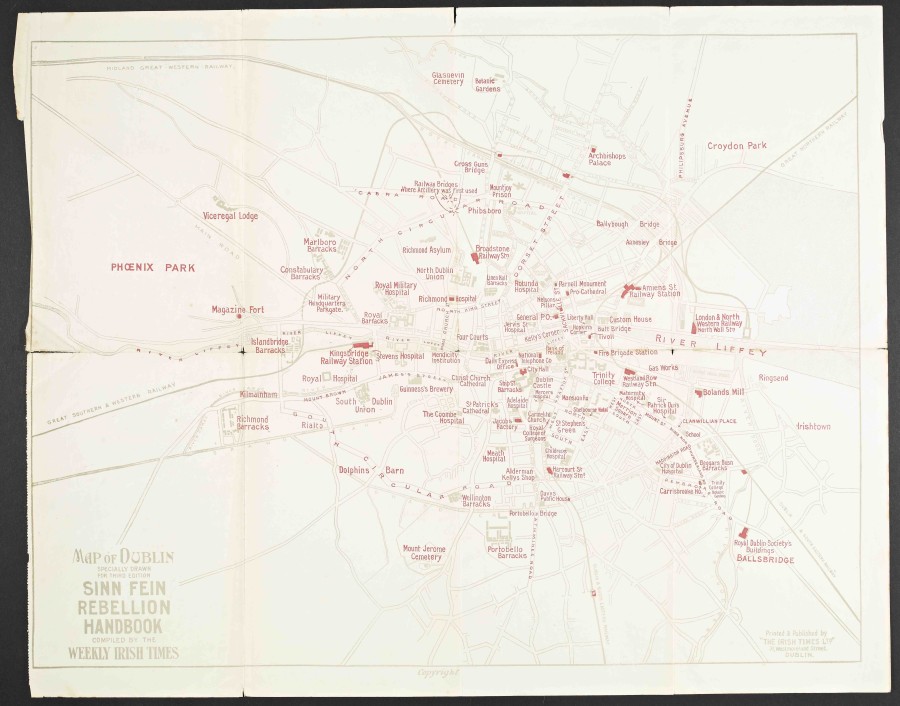

This map shows the rebel garrisons, British Army barracks, hospitals, police stations, railway stations, prisons, fire stations, bridges and telephone and postal centres.

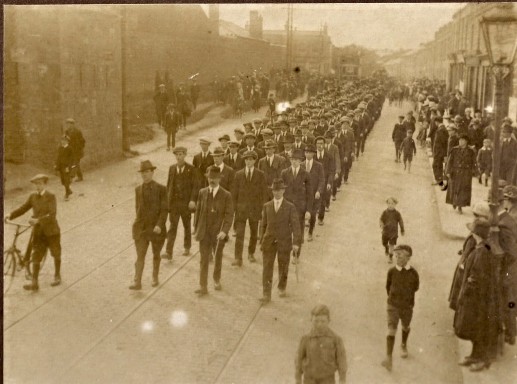

The rebellion lasts one week and at the end of it, around three thousand men and women are brought to Richmond Barracks.

The rebel leaders are court-martialled within Richmond Barracks.

Along with 22 other women, Rose McNamara and Marcella Cosgrove serve in Marrowbone Lane Garrison.

This plaque is near the Fatima Luas stop, about a 30-minute walk from Richmond Barracks.

The rebel leaders are court-martialled within Richmond Barracks.

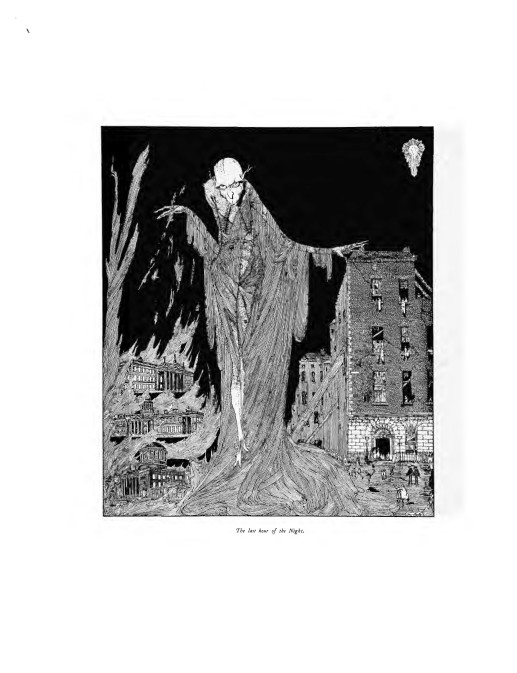

Main newspapers condemn the rebellion and the pro-Unionist Irish Times calls it ‘An Orgy of Fire and Slaughter’.

Captain Bowen-Colthurst of the British Army is tried for the unlawful killing of pacifist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington.

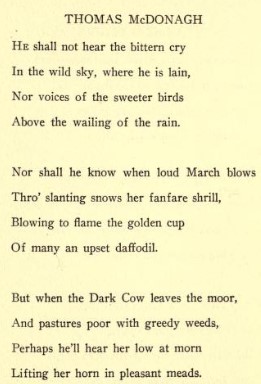

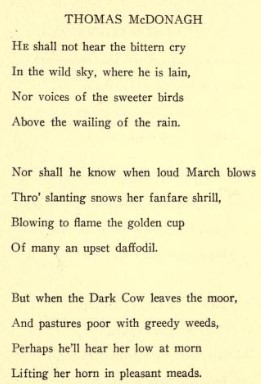

The poem, Thomas McDonagh, written by Francis Ledwidge

Having served in Gallipoli, Francis Ledwidge is injured and returns to Dublin on leave.

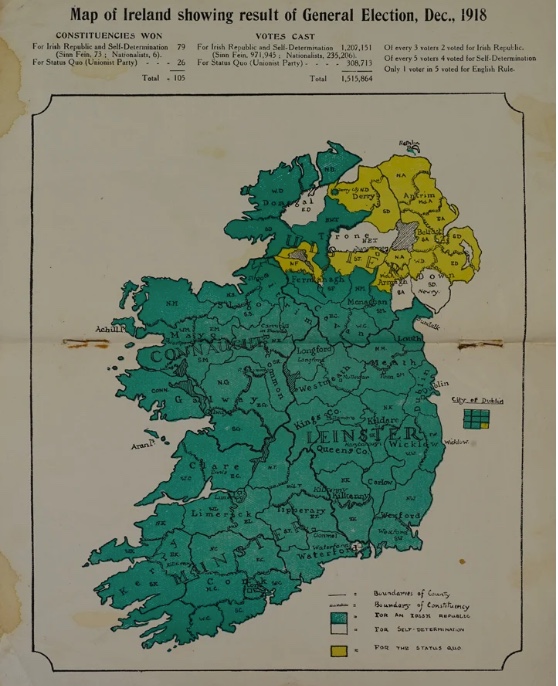

A general election sees the Nationalist party, Sinn Féin, win a landslide victory over the whole of Ireland.

The first Dáil Éireann (Parliament) sits in Dublin

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State, Richmond Barracks is handed over to the Irish National Army.

Town planner Patrick Abercrombie proposes his Dublin of the Future

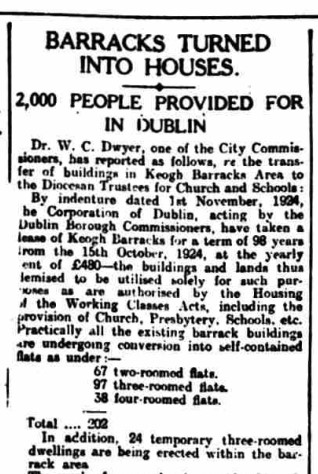

Kehoe Barracks is vacated by the Irish Army.

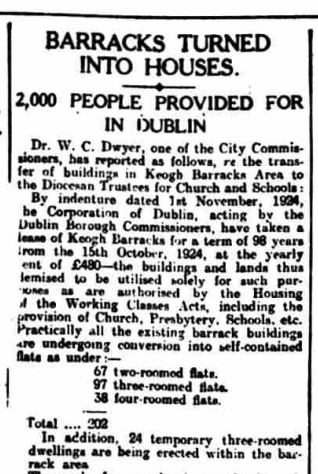

Kehoe Barracks is handed over to Dublin Corporation to house ‘the poorer class of workers’.

The former garrison chapel used by soldiers becomes the church of St. Michael of the Angels

The Christian Brothers open St Michael’s school in the old recreation rooms and the gym.

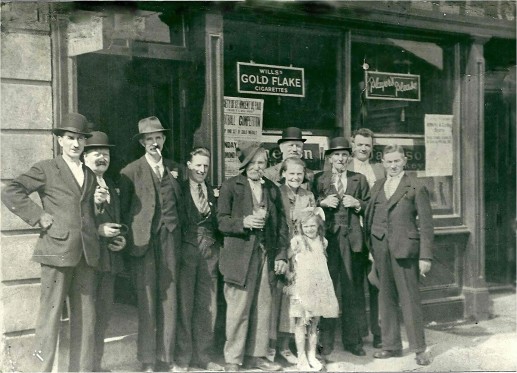

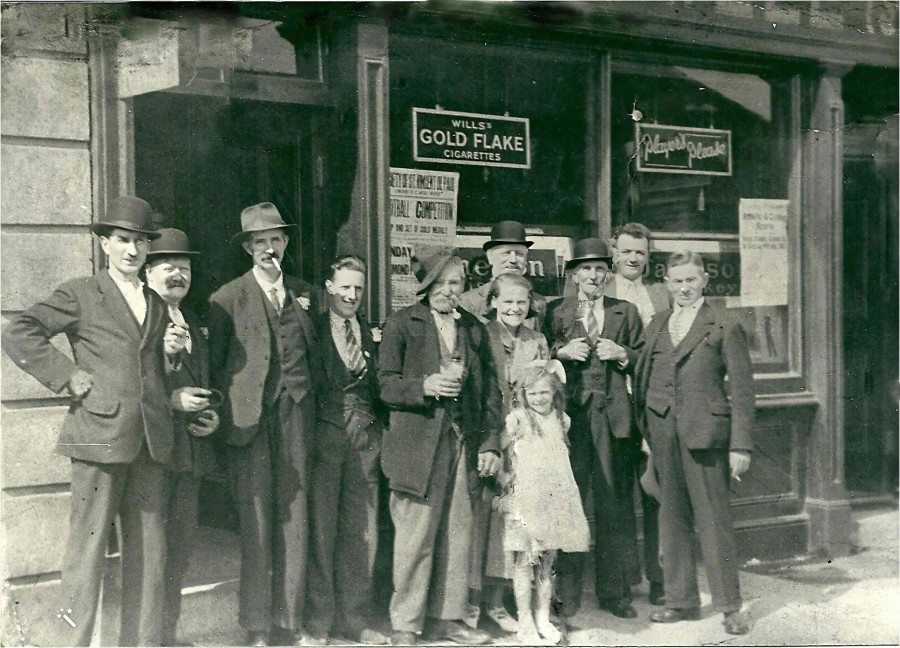

Hundreds of families live in Keogh Square.

Most of the barracks is demolished to make way for new public housing.

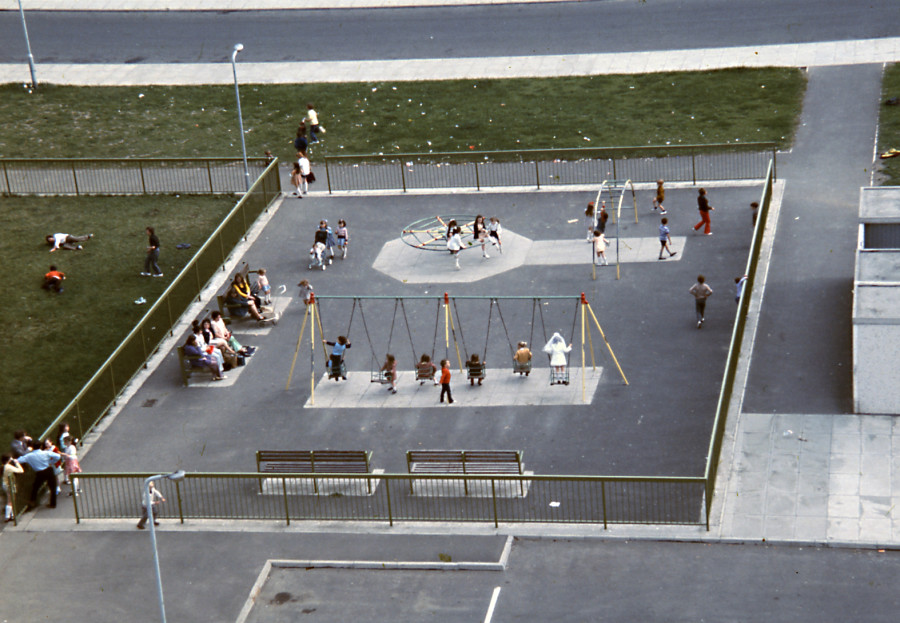

St Michael's Estate is built by Dublin City Council on the site to house working-class families and the elderly.

St Michael’s Estate begins to deteriorate.

St Michael's Christian Brothers school closes.

Plaque to Francis Ledwidge

The Health Services Executive opens a Primary Care centre in one section of the old barracks.

The last block of St Michael's estate is demolished.

Renovation begins.

The restoration process.

The local community attends the launch of the Richmond Barracks renovations.

Richmond Barracks opens as a museum with tours of the gymnasium.

Local group, The Yarn School, create a Commemoration Quilt in honour of the seventy seven women detained in Richmond Barracks in 1916.

Richmond Barracks becomes a cultural centre.

With thanks to:

Further reading from your local library

Map of Inchicore before Richmond Barracks was built. John Rocque map of 1775.

In 1800, before the building of the barracks, Inchicore was a mostly rural area with windmills powering flour and paper mills along the Camac River.

The Great Southern Mail Coach Road, which is now Emmet Road, was the main highway from Dublin to the west of Ireland.

You could find inns and taverns along the road. The area changed largely over the years as trades and businesses developed nearby.

This early drawing of Richmond Barracks (from around 1820) also shows a cabin which is most likely a bleaching house for linen. A sitting figure on the right is, perhaps, playing an instrument or reading a paper.

The British government has become alarmed at the threat of attack from the French as well as Irish revolutionaries and embarks on a campaign of building army and police barracks and martello towers throughout Ireland.

Richmond Barracks is completed but it will be four years before it is occupied. It can accommodate 1,200 men and 25 horses and is one of the British Army's largest barracks in Dublin.

It is named after Charles Lennox, the 4th Duke of Richmond, who is the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and acts as the British Crown's representative in Ireland. Lennox is a direct descendent of Charles II and a cousin of the United Irishman Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

From Lennox’s perspective, it is not a very attractive position, as the Act of Union in 1801 has resulted in the dissolving of Grattan’s Parliament and much of the aristocracy and wealth, as well as politicians, are leaving the city.

("From Richmond Barracks to Keogh Square" by Liam O’Meara)

The site of Richmond Barracks was chosen because the Grand Canal passes by one side of it and the Great Southern Mail Coach Road (now Emmet Road) passes by the other side.

This enabled the easy movement of troops from the barracks to suppress unrest or rebellion.

The Royal Cheshire and Lancashire Regiments are the first men to occupy the barracks.

On 21 June, a ball is held at Richmond Barracks to mark the start of it as a working barracks and the dancing continues until 6 am. It may be noted that this was for officers only and the soldiers and public were not invited.

The newspaper, Saunders News-letter, reported:

‘On Tuesday evening, the 21st June, the officers of the 3rd or Prince Regent’s Lancashire Regiment, stationed at Richmond Barracks, gave a most elegant ball and supper to a numerous and fashionable party of their friends.

Muskets, swords, pistols and other military weapons were fancifully disposed through the room interspersed with flowering shrubs and evergreens’.

(Saunders Newsletter 21 June 1814)

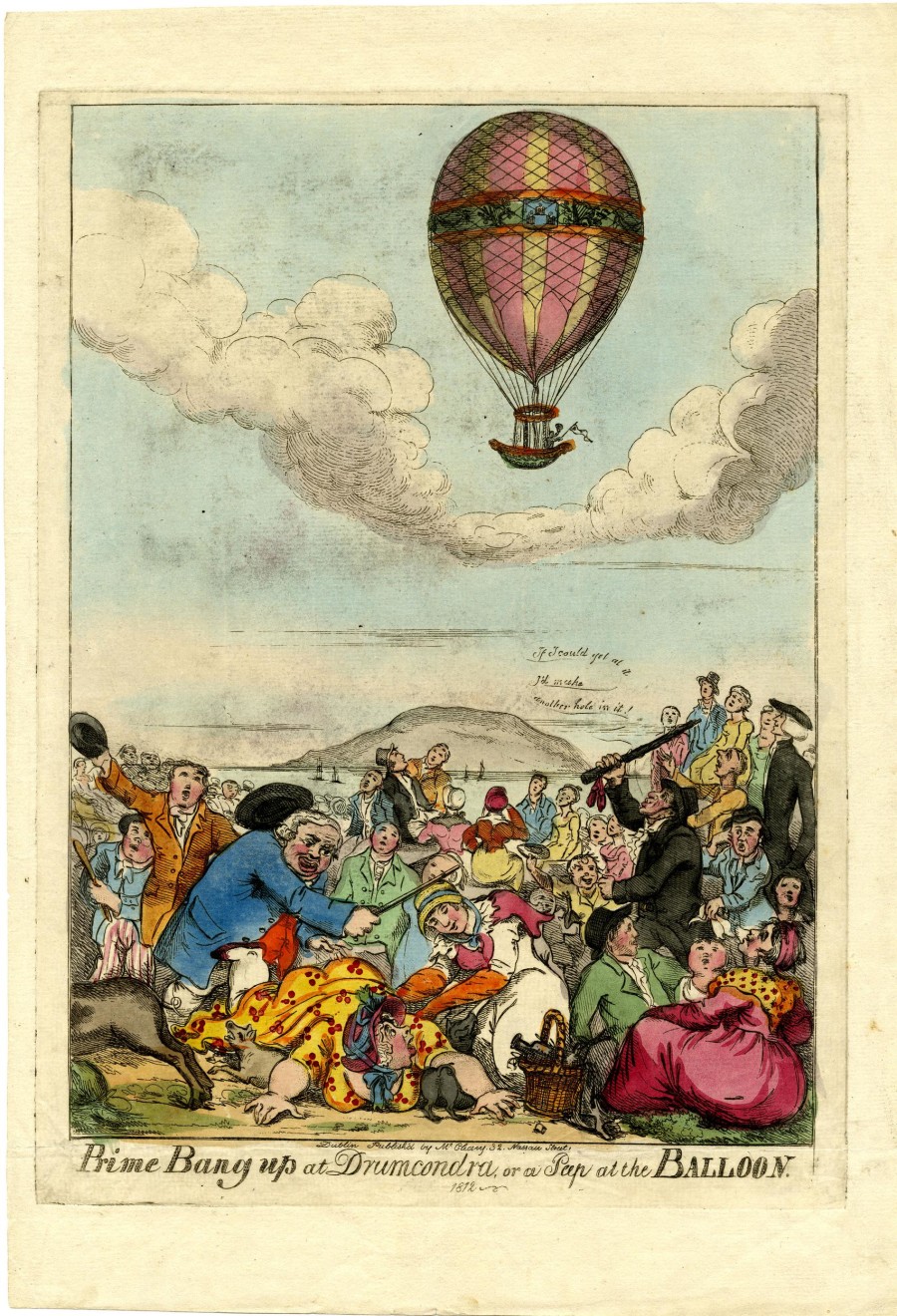

Large numbers of locals are admitted when Mr Sadler’s hot air balloon ascends from Richmond Barracks to the delight of the soldiers and the general public who ‘poured forth on every avenue leading to Kilmainham’ on 5 November.

The English balloonist, Windham Sadler, and his co-pilot Edmund Livingston, land in a bog near Edenderry but are led to safety by a barking dog! Sadler has already ascended a balloon in Cork and goes on to make the first successful balloon flight across the Irish Sea in 1816.

(Dublin Evening Post 1816)

There is always a possibility that soldiers will organise a mutiny or rebellion and refuse to take orders from the top men in the army. Punishments can be harsh for this.

The Dublin Weekly Register reports that in Richmond Barracks there are ‘discontents in the soldiery’ in the 81st Regiment and one man is chosen to be punished.

He is sentenced to 1,000 lashes and when the other soldiers hear this, 300 of them ‘broke out into open mutiny’. The rest of the soldiers are ordered to stop the mutineers and only when the lashes are given, is ‘tranquillity restored’.

The crop failure of last year has resulted in agrarian unrest in many parts of Ireland and a group known as the Whiteboys, who have already burnt police barracks in Cork, are thought to be about to attack Richmond Barracks. The Oxfordshire Regiment prepares itself in readiness and though the attack never happens, the pattern of crop failure and evictions leading to civil unrest and underground groups agitating for rebellion will be repeated throughout the nineteenth century.

("From Richmond Barracks to Keogh Square" by Liam O’Meara)

The Saunders Newsletter reports that the Oxfordshire Regiment from Richmond Barracks helped fight a fire at the Hibernian Woolen Mills in nearby Kilmainham, along with fire engines supplied by the Arthur Guinness company and assistance from the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. (Saunders newsletter 2 February 1822)

The Catholic Association and Daniel O’Connell ‘The Liberator’ open Goldenbridge Cemetery where Catholics can be buried. O’Connell is calling for more rights and freedoms for the Catholic majority.

Click here to learn more about Goldenbridge Cemetery tours.

The opening of Goldenbridge Cemetery was widely reported and the Dublin Morning Register gave this description:

‘..it is beautifully planted with every species of tree that is considered indicative of the melancholy and solemnity that should attach to a place devoted to the interment of those who were loved while living and whose departures in the cause of mourning and affliction to those who survive them…the Catholic Chapel in the burial ground will be of the greatest advantage and convenience to the Catholic soldiery stationed at Richmond Barracks'.

(Dublin Morning Register 16 October 1829)

A funeral described

A visitor to Ireland, Anne Plumptre, describes the Catholic funeral procession of a popular priest. As it leaves Sackville Street on its way to a burial ground four miles outside the city, she observes;

‘An immense concourse of people walking two-and-two, wearing white linen scarfs and hatbands preceded and followed the hearse; after them came a long train of carriages, coaches and chariots and last of all an almost equally long train of jaunting cars and jingles.’

(Narrative of a residence in Ireland during the summer of 1814 and 1815, by Anne Plumptre)

Incidents of public disturbance are reported, involving the soldiers and local people.

The Drogheda Journal reports that peace-officer McDowell appears to have taken an over zealous attitude when trying to control music and dancing in the Richmond Barracks area. He goes into two public houses on a Sunday evening to break up the fun and entered ‘Sheridan’s public-house, Kilmainham, where Thady Roe was fiddling away and a buxom lass with her partner, tripping it along “so gaily oh” to the tune of “Smash the Windows”. He seized the fiddle and bow and bore them off captive.’

Then, this ‘inharmonious limb of the law’ visited Cosgrave's public-house near Richmond Barracks where he found ‘the Munster piper, John Maguire, blowing away and his music "flying up to the moon". Two soldiers were caught drinking and ‘dancing a jig to the tune of the "British Grenadiers”. McDowell seized the pipes, untacked them in less than no time, put the puff out of them and carried them off with him under his arm’.

(Drogheda Journal 1830)

Within a couple of years, a temporary Chapel is built in Goldenbridge cemetery, not only for the ‘convenience of the neighbourhood’ but also to give ‘catechismical instruction to the poor children’.

The Dublin Morning Register newspaper also reports that the ‘Catholic soldiers stationed in the Richmond Barracks attend public worship here every Sunday and send their children to be instructed in the catechism’. This practice of religion so close to the barracks would have been viewed as providing a calming and moral presence in the area.

The 1840s is a decade of unrest with the Young Ireland movement pushing for independence from Britain. A cultural and political movement, Young Ireland is set up by Thomas Francis Meagher and William Smith O’Brien. The Commander of the Forces issues orders for all men to remain in barracks in Dublin so that they may be called on to deal with food riots and rebel clashes. Richmond Barracks prepares and is fortified in readiness for attack.

The Commander of the Forces issues orders for all men to remain in barracks in Dublin so that they may be called on to deal with food riots and rebel attacks. In response, Richmond Barracks is fortified in readiness for attack from an internal enemy.

The Cork Examiner reports ‘‘The most formidable preparations which have yet met the eye are to be seen at Richmond Barracks situate on the south side of the city, a little beyond Kilmainham, which are being put in a state of the most complete fortification with port holes, loop holes, embrasures, breastworks and all the other works deemed requisite by the science of war for successfully resisting the attacks of an enemy’. (Cork Examiner 17 November 1843)

The Dublin Weekly Register reports: ‘Fortifications are now in course of erection at Porotbello and Richmond barracks. Further arrangements are in progress for resisting a street insurrection in Dublin - the castle yard is impeded with sandbags and chevaux-de-frise have been prepared to assist the operations of the military in the streets.’ (chevaux-de-frise is an object of defence - a beam of protruding sharp stakes to defend against attack)

(Dublin Weekly Register 25 November 1843)

The potato crop fails in various parts of Ireland. The British government do little to help with their poor policies and contribute to the Great Famine/Gorta Mór. More than one million die, while two and a half million people emigrate. The population of Dublin rises substantially during the famine years as people arrive in the city to escape the disaster of hunger.

As food prices increase, an emergency meeting of the leaders of Dublin city concludes ‘’...the unparalleled distress of the poor of Dublin imperatively demands the utmost exertion of every Christian to lighten the distress of the destitute and stay the evils which would follow in the track of famine'. (Dublin Weekly Nation 26 December 1846).

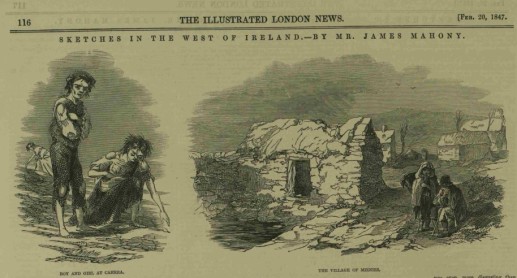

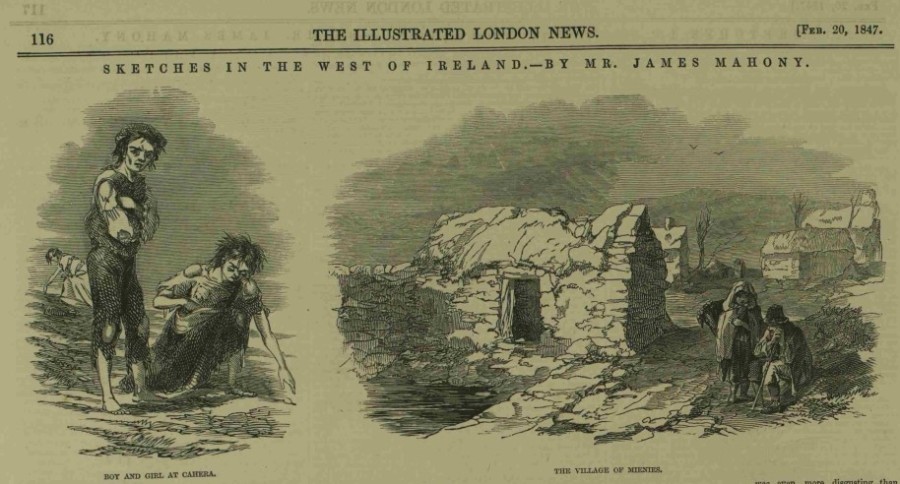

Newspapers begin to report on the Famine in Ireland as it grows steadily worse.

There are no known photographs of famine scenes in Ireland.

Illustrated London News, 20 February 1847

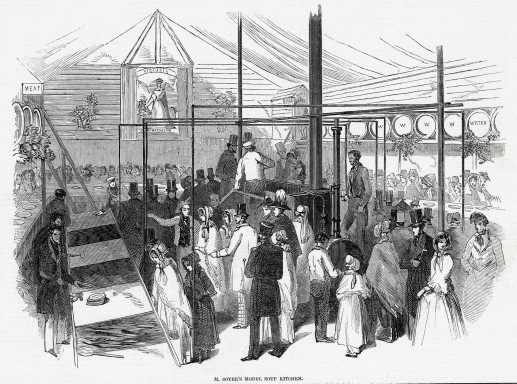

With government backing, the celebrity chef, Alexis Soyer, sets up a soup kitchen in front of the Royal Barracks (now Collins Barracks, across the Liffey from Richmond Barracks). Soyer creates a recipe for large quantities of soup that can be made into a ‘wholesome and cheap aliment for the millions’. He comments that by using his recipes ‘better support would be given to the poor at a trifling cost, and no one, it is hoped, hereafter, would hear of the dreadful calamity of starvation’. (Memoirs of Alex Soyer, London 1859)

Meanwhile, life goes on. The Great Southern and Western Railway (GSWR) line opens in Inchicore and becomes the area’s biggest employer. Railway workers move into specially built houses and businesses in the area flourish.

Inchicore Railway Works is where trains are fixed up, looked after and checked before being sent out to travel on tracks all over Ireland.

For many years, ‘The Works’, as it’s known locally in Inchicore, has played a huge part in people’s lives in the area. Around 2,000 people worked at its busiest, and many workers and their families lived nearby. It has also been a part of history, from the Lockout of 1913 to the ‘Emergency’ during World War Two.

The Works was set up by the Great Southern and Western Railway in 1846 and added to the employment already provided by nearby Richmond Barracks. The newly built barracks attracted new businesses and providers of food and services to the military. Specially built housing for railway workers and their families sprang up as did schools, sports grounds and other amenities to meet the needs of a growing population.

The Spa Road Works was also established to build trams, and a tram line opened between Inchicore and the city centre in 1878. Both the Works and Richmond Barracks have given Inchicore its unique flavour of industrial heritage but on a local and community level.

Inchicore Railway Works is still looking after trains today and is an important part of new railway developments.

Click here to watch a film on the history of Inchicore Works.

Dublin sees a severe outbreak of cholera and instructions are issued to the soldiers of Richmond Barracks;

‘Soldiers wives washing linen in the Canal at Richmond Barracks and Portobello Barracks will be deprived of all indulgence and turned out of barracks’ and the soldiers are warned that; ‘No soldiers are allowed to bathe in the River or Canals in or near Dublin but they may do so in the Sea at the end of the North and South Walls, under charge of Non-commissioned Officers’.

("From Richmond Barracks to Keogh Square" by Liam O’Meara)

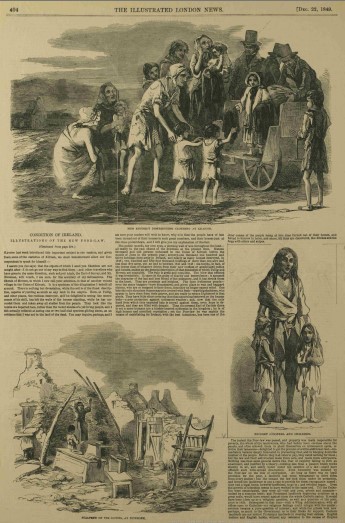

The sketch of Bridget O’Donnell and her two children is one that is often used to represent the Great Famine.

There are no known photographs of famine scenes in Ireland.

Illustrated London News, 22 December 1849

After six years of famine, the population of Ireland has fallen from 8.175 million (Census 1841) to 6.55 million (Census 1851) due to death, disease and emigration. In Dublin there are streets of overcrowded tenements and severe poverty and even the ‘better class’ and commercial areas are affected.

George Haskins, an American visitor to Dublin in 1851 wrote:

'...in the midst of all so rich and beautiful, a solemn, sad loneliness hung, like a black pall, about everything. The streets, though wide, were deserted; the stores, though lofty and built for long endurance, were closed; business there was almost none. Dublin was a deserted village, or a city of the dead.’ (George F. Haskins, Travels in England, France, Italy and Ireland, 1851)

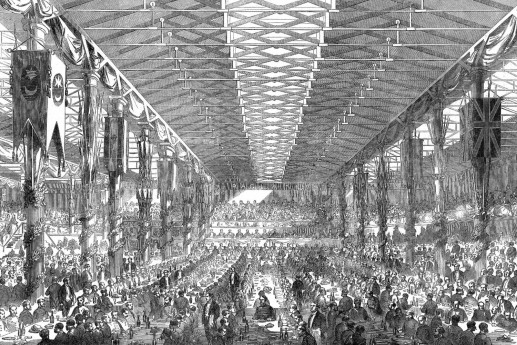

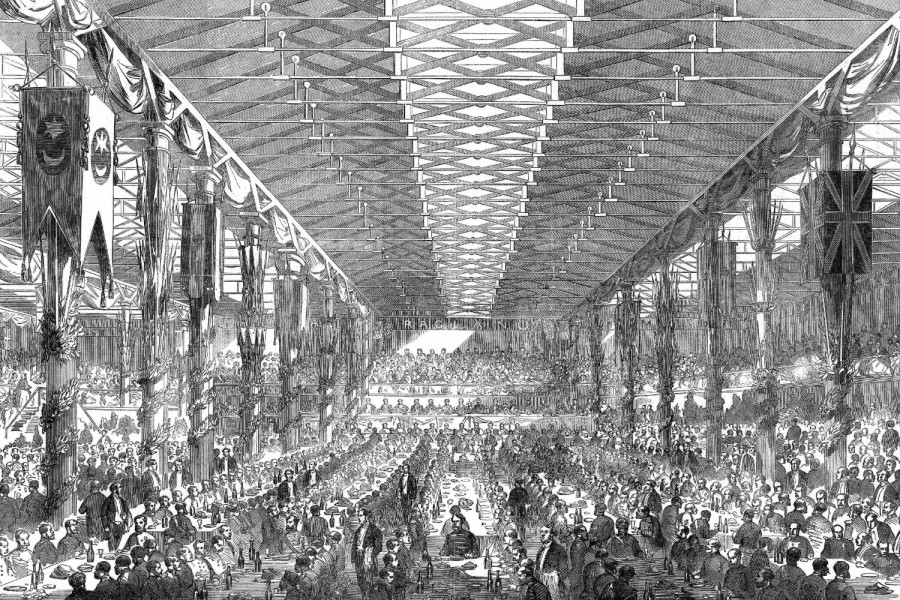

The Crimean War begins in 1853 and regiments of Richmond Barracks prepare to travel to the front.

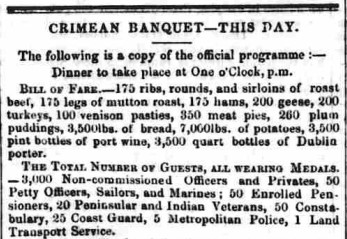

When the war ends in 1856, the Dublin Grand Crimean Banquet is held, with much pomp and ceremony for 5,000 soldiers, seamen and guests.

The image above is from the Illustrated London News on 8 November 1856.

The feast is lavish and it takes four vans alone to deliver the potatoes.

‘Much merriment was caused by the signal which passed along the crowds on the quay “Here comes the praties (potatoes) ” ..The cavalcade excited the general approbation of the young folk on the quay’

(Freeman’s Journal, 8 October 1856)

This being only a few years after the Great Famine, there would have been mixed reactions to such a display of feasting.

The Crimean Banquet is widely reported in newspapers and the Advocate included the menu:

MENU

175 ribs, rounds and sirloins of roast beef

175 legs of mutton

175 hams

200 geese

200 turkeys

100 venison pasties

350 meat pies

260 plum puddings

3,500 lbs. of bread

7,000lbs. of potatoes

3,500 pint bottles of port wine

3,500 quart bottles of Dublin porter

GUESTS

3,000 Non-commissioned Officers

50 Petty Officers, Sailors and Marines

50 Pensioners

20 Peninsular and Indian Veterans

50 Constabulary

25 Coastguard

5 Metropolitan Police

1 Land Transport Service

Life is harsh for the soldiers and their families as food and sanitation is poor.

In a report of military living conditions, it is stated that Richmond Barracks allows wives of soldiers, whose marriages have been permitted by the Army, to live in dormitories with their husbands. For this, and half rations, she must cook and clean for the men in her barrack room.

There are also 'She Barracks', a house where 'unapproved' wives of married soldiers live in a room rented by her husband for a 'small, weekly sum'. (Liam O’Meara).

("From Richmond Barracks to Keogh Square" by Liam O’Meara)

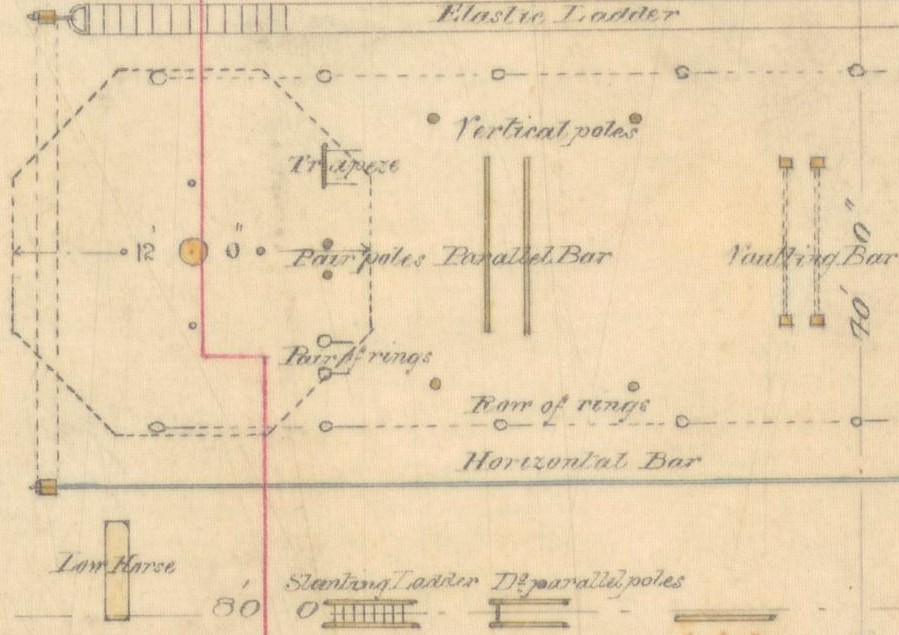

In another report the laundry facilities are listed and what is provided for children. There are enough children to require a school but also enough toddlers who need their own space. There is:

‘one woman’s wash house and an excellent laundry attached to the new married quarters with hot and cold water laid on. There is a drying closet properly heated with 21 clothes horses, an ironing room with benches, mangle and laundry stove; the arrangements are very satisfactory. The whole is lighted with gas. There is one chapel school and one soldier’s room has been misappropriated for an infant school. Another as a library. At one angle of the barrack enclosure married quarters have recently been erected for 80 families. Each room contains a cooking range and all are lighted with gas’.

(Barracks Report, Parliamentary Papers, 1863)

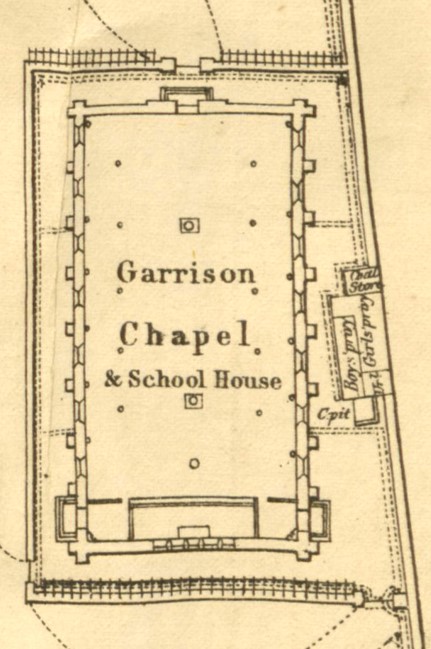

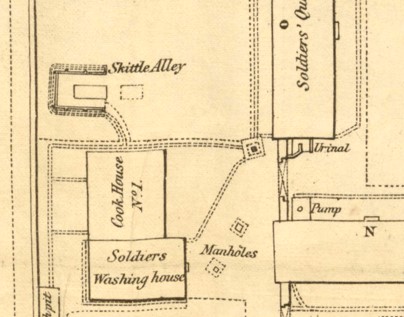

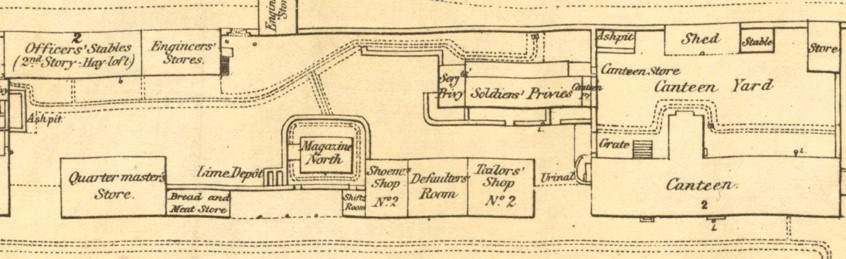

The barrack’s recreation rooms are opened, including a library and games room with plays and lectures taking place.

It is hoped that these diversions will keep soldiers occupied and discourage drinking and fighting with soldiers from other barracks.

Games of skittles (similar to bowling) are played in the two skittle alleys in the barracks.

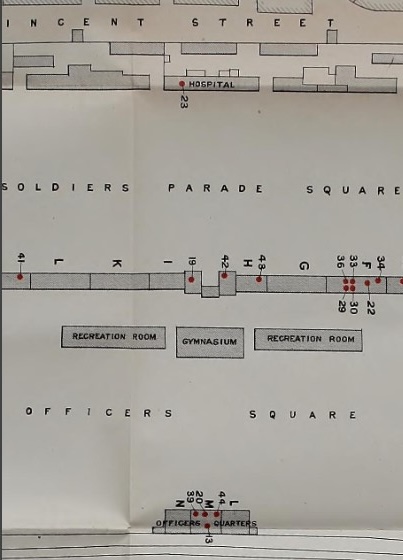

Larger barracks like Richmond had services on site such as tailor’s, shoemaker’s, and bread and meat stores as can be seen in the plan (second photo).

Separate Officers’ stables, stores and a canteen are also visible.

Amateur theatrics in military barracks were open to the public and provided opportunities for lower army ranks to socialise with local populations.

This poster advertises three short dramas by the ‘Amateurs of the 40th Regiment’, in the recreation room of Richmond Barracks, Dublin. To catch the attention of the public, the words ‘NEW Theatre Royal’ are in large font at the top of the poster. There were two enormous and popular theatres in late nineteenth century Dublin; the Theatre Royal in Hawkins Street and the Queen’s Royal Theatre behind Trinity College.

Interesting to note that the show started late, at 9.30 pm and the best ‘Reserved’ seats are 1s while ‘Children in arms’ are £1. 1s.

(Poster dated between 1852-1880)

The War Office (WO) attempts to have Goldenbridge Cemetery closed, citing health concerns. The WO claims there is too much disruption to the barracks, as the funerals are frequent. There is a public outcry but in two years Goldenbridge Cemetery closes to all but families that already have a plot here.

Disturbing rates of depression and suicides amongst soldiers motivates the army to build a gymnasium with a large, glass cupola, letting in light and air.

There would be an instructor of gymnastics and soldiers from nearby barracks were also expected to use it.

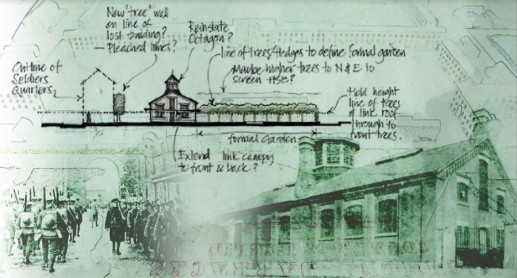

Plan of the gym in New Barracks in Limerick (now Sarsfield Barracks), which was an exact replica of the Richmond Barracks gym.

Due to an outbreak of typhoid or ‘enteric fever’ the War Office writes a report on the sanitary conditions in Richmond Barracks. It is considered very important for rooms to be well-ventilated and it is noted that;

‘In the married soldiers' quarters there are a considerable number of rooms in which the cubic space is below the normal amount per head (even when reckoning that children only require half the space that an adult does) and several rooms in which it is very greatly below’ and ‘ the ventilation is deficient.’

The outbreak of enteric fever is so bad that the report includes a map of who has caught it and where in the barracks they slept. (see map above).

The gymnasium and recreation rooms can be seen in the middle, beside the soldiers quarters, marked L, K, I, G etc. (Sanitary Report of Richmond Barracks 23 July 1889)

The second Boer war starts in South Africa and regiments in Dublin prepare to be deployed, including many Irish soldiers.

The 1913 Lockout is a city-wide industrial dispute resulting from Dublin employers locking out thousands of members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

Tram drivers based in Inchicore play a leading part in the dispute. Their branch of the ITGWU meets in Emmet Hall at 122 Emmet Road.

There are several days of riots and ‘disturbances’ and the West Kent Regiment is called out from Richmond Barracks to attack the locked-out workers. Town Councillor Patrick Carrol is beaten to death outside Emmet Hall.

Throughout Dublin, workers and their families, an estimated 100,000 in total, suffer greatly for the five-month duration of the strike. While it ends in defeat for the workers, it acts as a catalyst for the Trade Union movement in Ireland.

As a result of the police violence against strikers and citizens, the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) is formed to “prevent the brutalities of armed thugs occurring in the future” (James Connolly, 1914).

Emmet Hall at 122 Emmet Road was home to Michael Mallin, strike leader and Commandant of the ICA.

Visit the site of Emmet Hall at 122 Emmet Road. It is on the right-hand side as you travel towards Dublin city centre.

This cartoon references the tramcar used to bring the military to the Howth gun-running landing in 1914.

William Martin Murphy owned the tram company that went on strike in 1913 and fatalities listed were as a result of police brutality.

In 1913, as Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell had allowed Northern Unionists to bring guns into the northern province of Ulster which resulted in the formation of a nationalist Volunteer movement in the South. The Volunteers brought guns into Howth Harbour in 1914.

The cartoon reads:

‘In Memoriam of Patrick Quinn (Irish Transport Union); Mrs Duffy wife of Owen Duffy (Irish Transport Union); and James Brennan murdered July 26th 1914; James Nolan, John Byrne, murdered August 1913; and Alice Brady murdered December 18th 1913.

William Murder Murphy’s Tramcars - Lest ye forget! Murphy ordered civilian passengers out of his cars to facilitate Birrell’s hired assassins and the police in their ignoble attempt to disarm Irishmen. These sweepings of Scotch slums shot down unarmed men women and children.’

War is declared and troops are sent from Britain to the many barracks in Dublin to prepare them for the Western Front. About 21,000 Irish men are serving in the British Army as war breaks out; as it progresses, another 47,000 join up.

It is estimated that 30,000 to 35,000 Irish soldiers will die in WW1. The war splits the nationalist movement in Ireland, with some joining the British army and others continuing with the campaign for independence.

The poet Francis Ledwidge joins the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and is one amongst many young Irishmen who serve at Richmond Barracks.

As a writer he has been supported and encouraged by Lord Dunsany. With his brother Joseph, they found the Slane branch of the nationalist organisation, the Irish Volunteers.

Though sceptical at first of the conflict, his viewpoint changes, particularly when Meath, his home county, embraces the war effort.

A sculpture of Francis Ledwidge is within Richmond Barracks as well as a plaque to him at the end of the HSE medical centre as you walk to Emmet Road.

The sculptor is Rory Breslin and both it and the plaque were commissioned by the Inchicore Ledwidge Society.

Wives of Irish soldiers in the British Army receive a ‘separation allowance’ and are popularly known as ‘separation women’. The higher the military rank of the soldier and family size, the higher the payment.

The poster lists more categories of payment; for dependents of unmarried men and widowers, adopted children and motherless children. Another poster declares:

‘Enlist today and your dependents will be well provided for’

Conscription is not enforced in Ireland and there is a variety of reasons why men join up to participate in the war: The promise of Home Rule, for the pay it offers, the cause and for adventure.

Support for Irish independence from Britain grows and the Irish Republican Brotherhood plans an all-island rebellion but due to a series of mishaps it takes place mostly in Dublin.

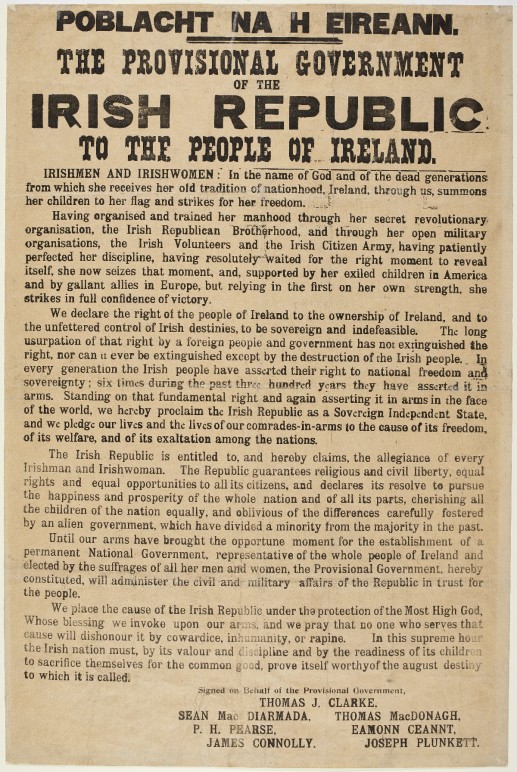

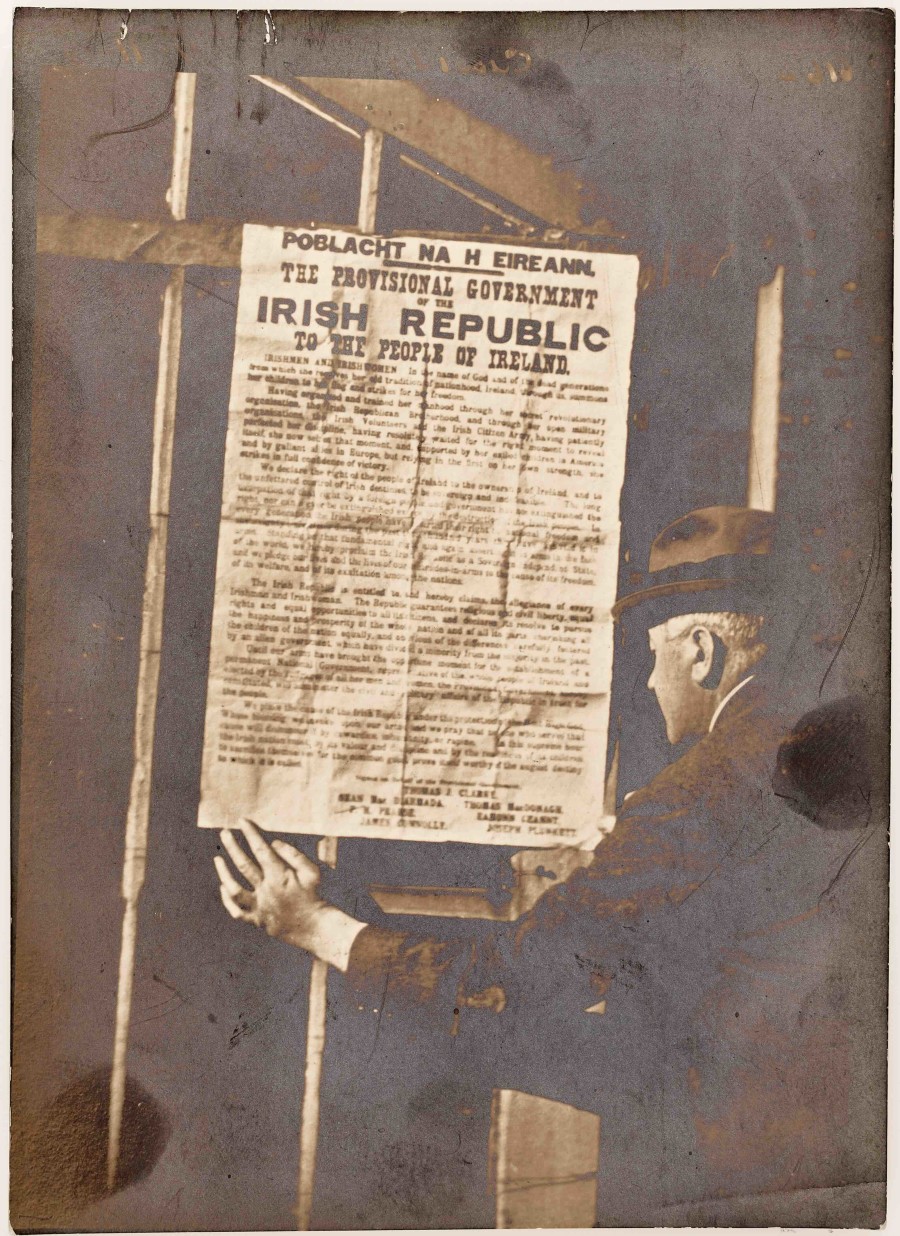

The rebellion starts on Easter Monday with the reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and several rebel garrisons are set up, including one in the South Dublin Union workhouse close to Richmond Barracks.

As fighting begins, troops are dispatched from Richmond Barracks to the Union to suppress the insurgents.

Around eighteen hundred rebels participate in what comes to be known as the Easter Rising or Easter Rebellion, and it lasts one week.

A declaration of independence is written and signed by the seven leaders often referred to as ‘the Proclamation’. Patrick Pearse reads it out on the steps of the General Post Office on the first day of the rebellion and it is posted up all over the city.

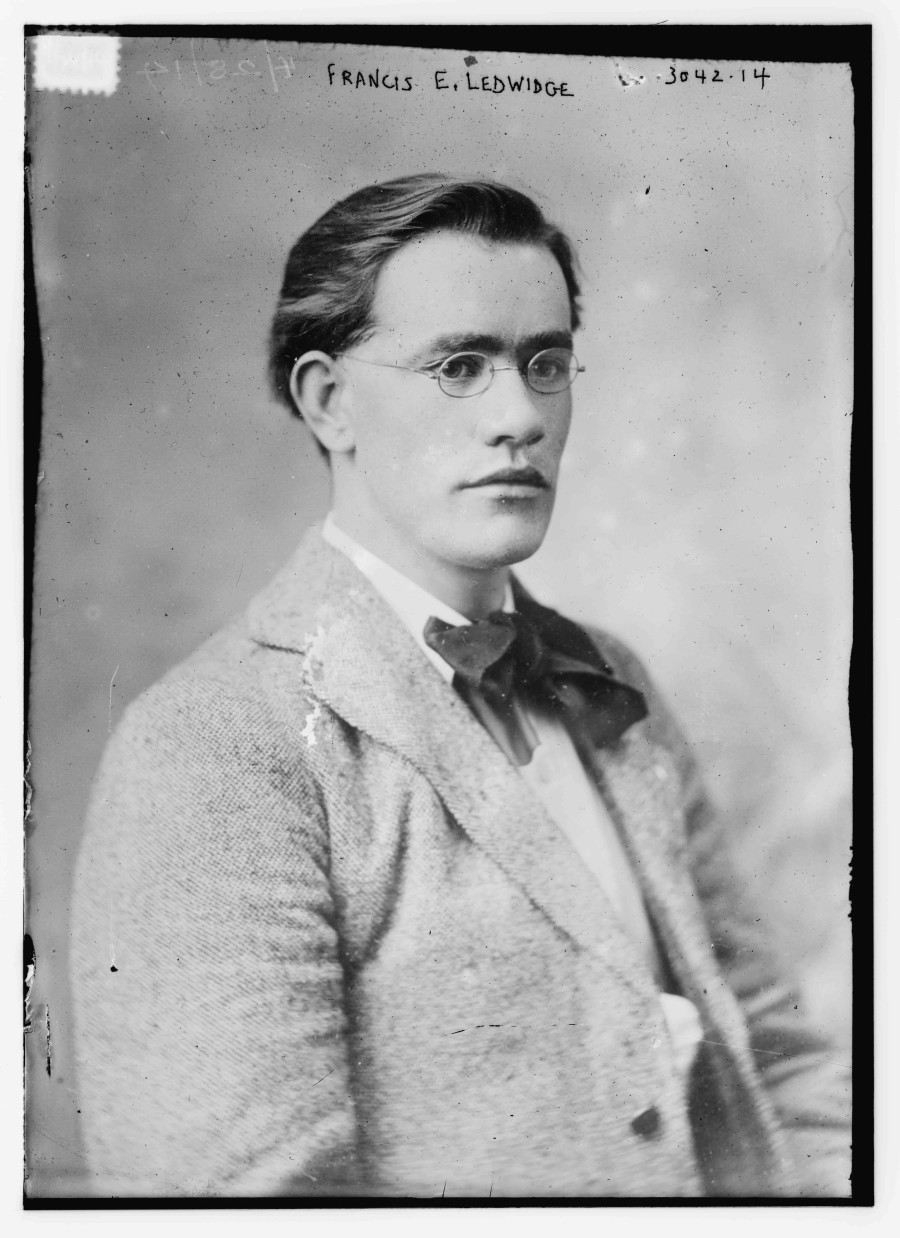

This map shows the rebel garrisons, British Army barracks, hospitals, police stations, railway stations, prisons, fire stations, bridges and telephone and postal centres.

It has a more military aspect to it as it was included in the ‘Sinn Fein Rebellion Handbook’ by the pro-Unionist newspaper The Weekly Irish Times. The handbook describes the actions and people of the rebellion but overall the paper is against insurrection. It includes heroic stories about the British armed response and brave civilians helping the wounded.

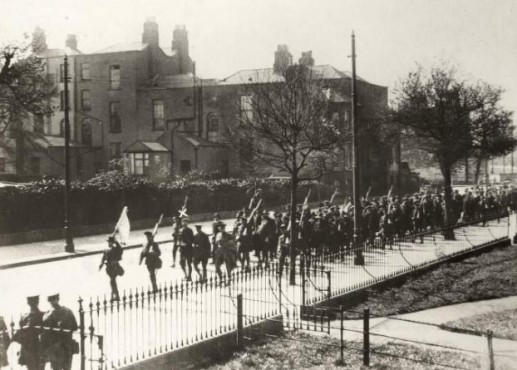

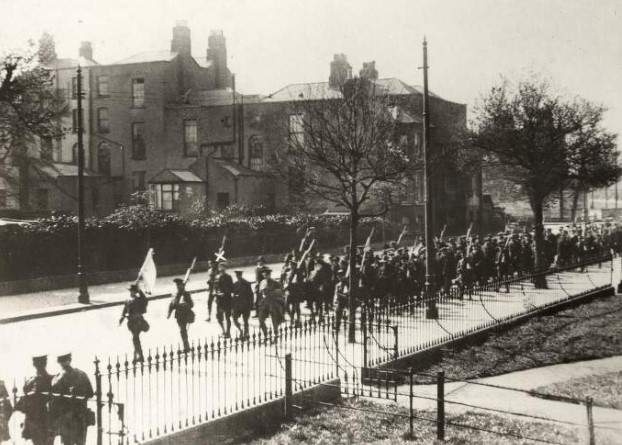

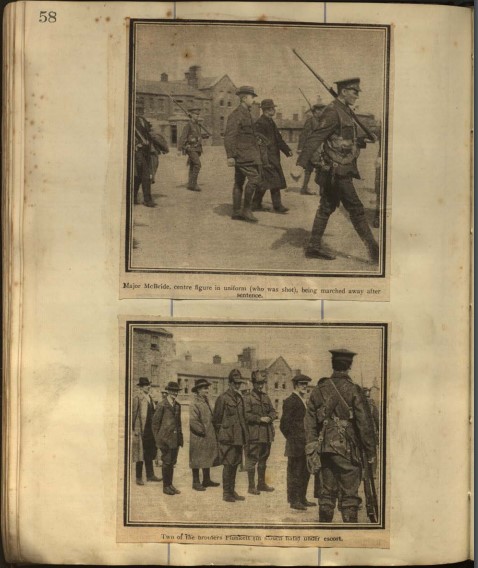

The rebellion lasts one week and at the end of it, around three thousand men and women are brought to Richmond Barracks as prisoners including Michael Collins, Éamon De Valera, Constance Markievicz and Dr Kathleen Lynn.

People are part of different groups; Cumann na mBan, Irish Volunteers, Na Fianna Éireann and the Irish Citizen Army.

The first group to arrive had been fighting in nearby Marrowbone Lane Garrison and Annie Cooney was one of the seventy-seven women detained. She later recalled that they smuggled guns in as they entered the barracks, which had been given to them by the Volunteers. Held in the married quarters they ‘found a couple of ledges at the side of the chimney and stuck them up there. We felt satisfied that we had not handed them over to the British Army anyway..’. Annie described the food:

‘A British military sergeant had charge of us and brought tea in a bucket and some hard biscuits which we called dog biscuits. He apologised for the sort of food he had to give us’. All the women are released apart from Markievicz.

Irish Volunteer Piaras Beaslaí, remembered the processing of prisoners;

“They were placed sitting on the floor of the gymnasium, and the political detectives of the G Division of the Dublin Police came like a flock of carrion crows to pick out the suspects for court martial...Anybody who had seen that sight may be pardoned if he felt little compunction at the subsequent shooting of these same G Men."

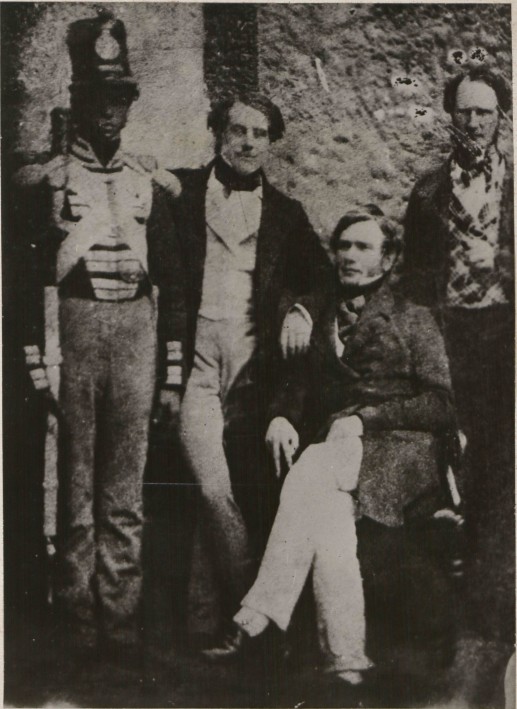

After being processed, most prisoners are either moved to nearby Kilmainham Gaol, released or deported to Britain. The rebel leaders are court-martialled within Richmond Barracks. This photo shows British soldiers standing at the left and right of four rebels who wear slouch hats, caps and a trilby style hat.

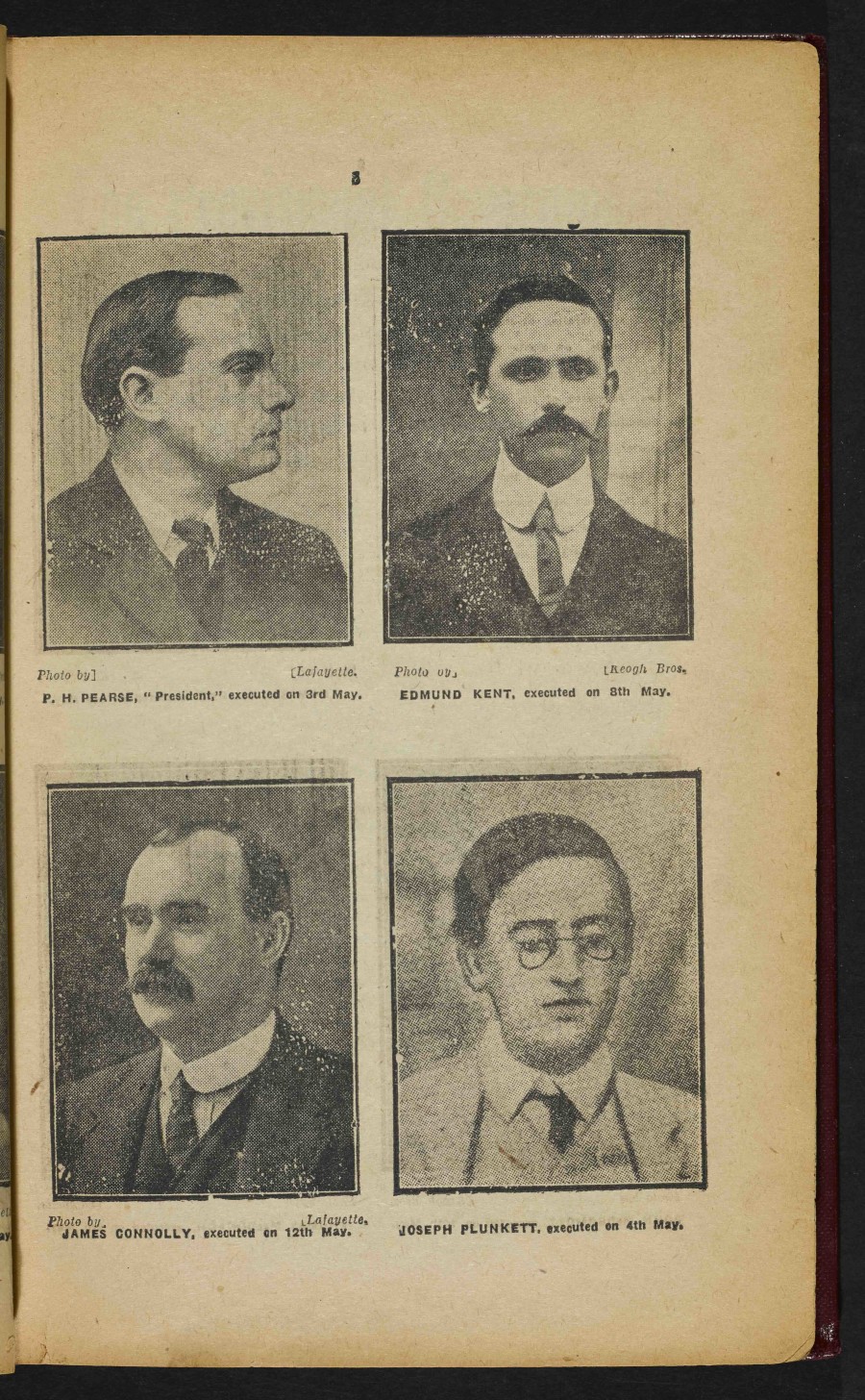

Markievicz is sentenced to death, but this is later changed to life imprisonment. Fourteen insurgents, including the seven signatories of the Proclamation, are executed in Kilmainham gaol; Thomas Clarke, Seán MacDiarmada, Thoma McDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly and Joseph Plunkett.

Click here to listen to Claude McGowan talking about his aunt Josie McGowan and her involvement as a Cuman na mBan member in the Marrowbone Lane Garrison.

Along with 22 other women, Rose McNamara and Marcella Cosgrove serve in Marrowbone Lane Garrison.

Born in 1895 Rose is a member of Inghinidhe na hÉireann, an organisation that encourages women to campaign for their own rights as well as for Irish independence. Serving as Vice-Commandent in Cumann na mBan, Rose is brought to Richmond Barracks at the end of the Rising and transferred to Kilmainham Gaol.

Marcella Cosgrove is the Quartermaster of the Inghinidhe na hÉireann branch of Cumann na mBan.

As the young women are marched to Richmond Barracks, the girls sing all the time ‘amidst the insults of the soldiers and the people along the route’.

In the photograph, Marcella is wearing the official uniform as well as the distinctive Cumann na mBan membership badge (pictured) of the lettering sitting on a rifle.

Below is a list of the seventy-seven women held at Richmond Barracks in 1916.

Can you find your relation?

Good to know: The surnames are listed from A to Z.

‘Née’ means the woman’s name before she married.

‘Later’ means her later married name.

Kathleen ‘Katie’ Barrett (née Connolly)

Bridget ‘Brigid’ Brady (later Murphy)

Kathleen Browne

Martha Browne

Eileen Byrne

Katie Byrne

Mary ‘May’ Byrne (later Doyle)

Winifred ‘Winnie’ Carney (later McBride)

Máire (Mary/May/Meg/Maura) Carron

Annie Cooney (later O’Brien)

Elizabeth ‘Lily’ Cooney (later Curran)

Eileen Cooney (later Harbourne)

Marcella Cosgrove

Bridget Davis (later O’Duffy)

Ellen ‘Nellie’ Ennis (later Costigan)

Madeleine ffrench-Mullen

Kathleen ‘Kitty’ Fleming

Brigid ‘Bríd’/Bridget’ Foley (later Martin)

Mary ‘May’ Grahan (later O’Carroll)

Helen ‘Nellie’ Gifford (later Donnelly)

Bridget ‘Bridie’ Goff

Julia (Sheila/Sighle) Grenan

Roseanna ‘Rosie’ Hackett

Bridget Hegarty (later Harmon)

Anne ‘Annie’ Higgins/O’Higgins

Ellen ‘Nell’ Humphreys (née O’Rahilly)

Margaret ‘Maggie’ Joyce

Catherine ‘Katie’ Kelly

Josephine Kelly (later Greene)

Martha Kelly (later Murphy)

Margaret ‘Loo’ Kennedy

Bridy Kenny

Catherine ‘Katie’ Liston

Mary Liston

Elizabeth ‘Bessie’ Lynch (later Kelly)

Kathleen Lynn

Brigid Lyons (later Lyons Thornton)

Agnes MacNamee/McNamee

Kathleen ‘Katie’ Maher

Constance Markievicz (née Gore-Booth)

íd S. Martin

Kathleen ‘Kate’ Martin

Julia McCauley

Josephine ‘Josie’ McGowan

Margaret ‘Maggie’ McLoughlin

Rose McNamara

Florence ‘Flossie’ Meade (later Griffin)

Caroline ‘Carrie’ Mitchell (later McLoughlin)

Helena Molony

Pauline Morkan (later Keating)

Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Mulhall

Roseanna ‘Rose’ Mullally (later Farrelly)

Kathleen Murphy

Bridget Murtagh (later O’Daly)

Annie Norgrove (later Grange)

Emily Norgrove (later Hanratty)

Lily O’Brennan

Nora O’Daly (née Gillies)

Margaret ‘Cissie’ O’Flaherty (later Timmons)

Sheila O’Hanlon (later Lynch)

Emily O’Keeffe/O’Keefe (later Hendley)

Josephine ‘Josie’ O’Keeffe/O’Keefe (later McNamara)

May O’Moore (later Wisely)

Louisa O’Sullivan (later Pollard)

Mary O’Sullivan (later O’Carroll)

Mary Partridge (née Hamilton)

May ‘Mary’/’May’ Perolz (later Flanagan)

Countess Mary Josephine Plunkett (née Cranny)

Maria Quigley (later Clince)

Priscilla ‘Sheila’ Quigley (later Kavanagh)

Barbara Retz/Reitz

Catherine ‘Kathleen’ Ryan (later Treston)

Ellen Mary ‘Nell’ Ryan

Mary Kate ‘Kit’ Ryan (later O’Kelly/Ó’Ceallaigh)

Kathleen ‘Catherine’ Seery (later Redmond)

Jane ‘Jinny’ Shanahan

Josephine (Spicer) Spencer

(with thanks to Mary McAuliffe and Liz Gillis Richmond Barracks: We were there - 77 women of the Easter Rising).

Discover more about the lives of 77 women in the book Richmond Barracks: We were there - 77 women of the Easter Rising, by Mary McAuliffe and Liz Gillis. Published by Dublin City Council, 2016. You will find copies in your local library.

Click here to see more rebellious women on the Museum of Ireland website.

This plaque is near the Fatima Luas stop, about a 30-minute walk from Richmond Barracks.

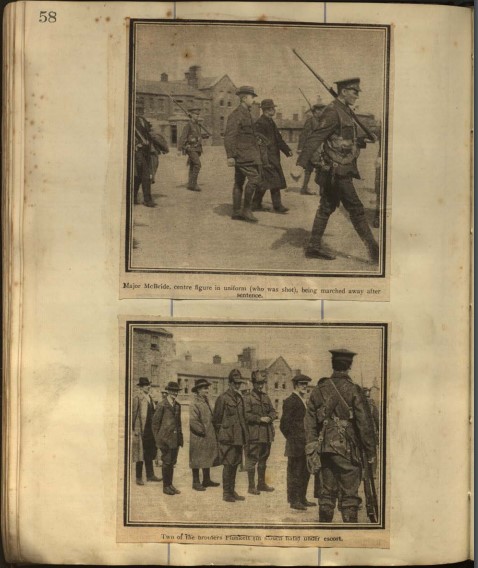

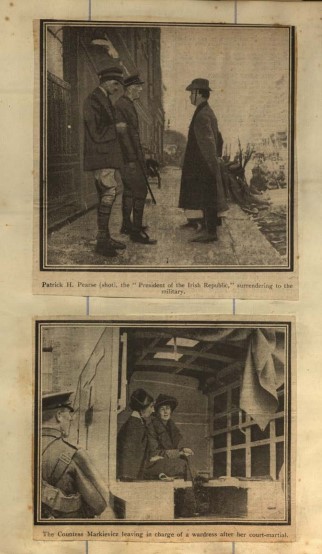

The rebel leaders are court-martialled within Richmond Barracks, in buildings where the Hollybrook nursing home is now, overlooking the garden.

A court-martial is a military court led by Army officers with no legal qualifications and no judge. 159 men and one woman are tried in this way. The prisoners are not allowed to represent themselves or be made aware of the rules of the court. Lawyers, the press and the public are not allowed to attend. Most trials last less than 20 minutes.

Around 3,000 people were arrested during the 1916 Easter Rising and taken to Richmond Barracks.

People made their own scrapbooks of news by collecting newspaper clippings of the rebellion. These photographs were cut from a 1916 newspaper and pasted into a scrapbook. It was donated to the Irish Military Archives by Mrs Geraldine Dillon(formerly Plunkett), daughter of Count Plunkett. He also took part in the rebellion.

The top photograph is of the surrender of Patrick Pearse (on the right) and Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell on 29 April 1916, at the end of the Easter rebellion.

O’Farrell is standing on the other side of Pearse and her boots can be seen in front of his shoes. This image has been reproduced many times and often O’Farrell’s boots were missing, either airbrushed out or because the image was getting cleaned up.

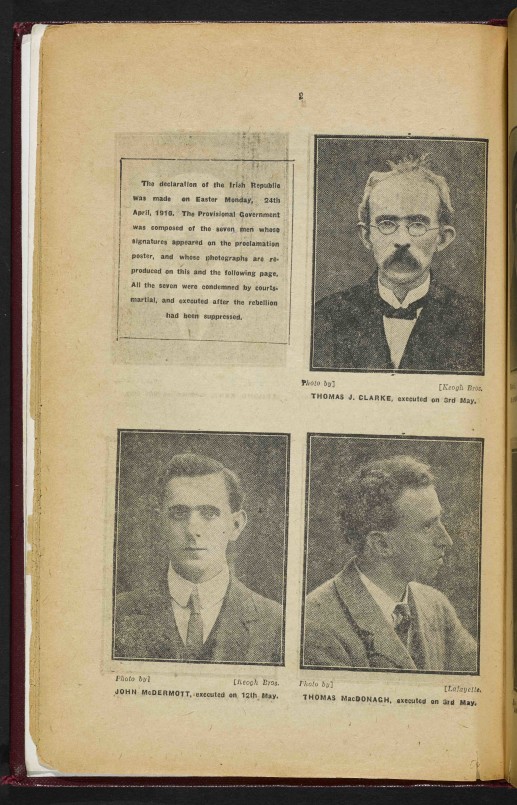

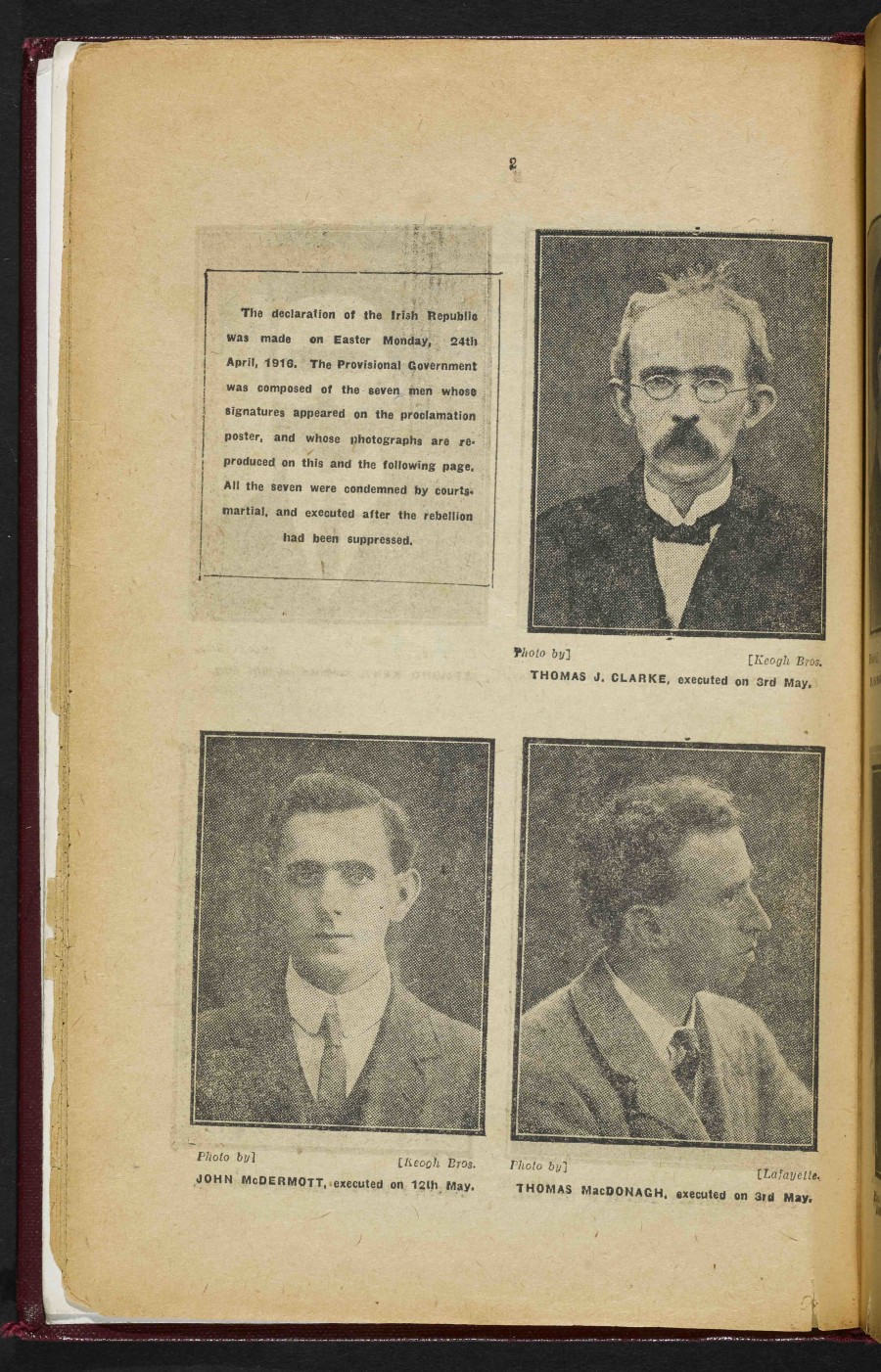

Main newspapers condemn the rebellion and the pro-Unionist Irish Times calls it ‘An Orgy of Fire and Slaughter’.

They publish the ‘Sinn Fein Rebellion Handbook’ as a record of a revolution that should not have happened.

The handbook includes photos of the leaders with words reassuring readers that they have had a fair hearing in a court and been punished.

The Irish Times reports:

‘The declaration of the Irish Republic was made on Easter Monday, 24th April, 1916. The Provisional Government was composed of the seven men whose signatures appeared on the proclamation poster and whose photographs are reproduced on this and the following page. All the seven men were condemned by courts-martial, and executed after the rebellion had been suppressed.’

The seven men were:

Thomas Clarke, executed 3 May

Padraig Pearse, executed 3 May

Éamon Ceannt, executed 8 May

Seán McDiarmada, executed 12 May

Thomas MacDonagh, executed 12 May

James Connolly, executed 12 May

Joseph Plunkett, executed 4 May

In June, there is another court martial but it is of Captain Bowen-Colthurst of the British Army who is tried for the unlawful killing of pacifist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington.

Here, his wife Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington (far right) arrives at Richmond Barracks to attend the hearing with her sisters Mary Sheehy-Kettle and Kathleen Sheehy Cruise O’Brien and friend Meg Connery.

Credit: National Library of Ireland.

Click the link below to listen to the poem ‘Thomas McDonagh’ by Francis Ledwidge read by Liam O'Meara.

Francis Ledwidge serves in Gallipoli, is injured and returns to Dublin on leave.

He appears to have become disillusioned with warfare as he mourns his friend Thomas McDonagh, executed as a leader of the Easter Rising.

Ledwidge is later killed in the battle of Ypres in Belgium.

A general election sees the nationalist party Sinn Féin win a landslide victory over the whole of Ireland (green areas on map) with the exception of the North East where Unionist and pro-British areas vote to stay within the United Kingdom (orange areas on map).

This map was published by the ‘Friends of Irish Freedom’ based in New York and the 1916 Proclamation is quoted at the bottom.

It highlights the lower population numbers after the Famine, calling it the ‘Result of English rule’ and proclaim that

‘GOD Irrevocably Fixed the Boundaries of IRELAND- Those of Poland, Czecho-Slavia, Jugo-Slavia, Serbia, Roumnia etc. have been fixed temporarily by politicians!’

The first Dáil Éireann (Parliament) sits illegally in Dublin and members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Cumann na mBan (women’s organisation involved in IRA activities) wage a guerilla war, the War of Independence, against British state forces.

The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment 3rd battalion arrive at the barracks and are absorbed into the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Regiment who remain in place until Richmond Barracks is handed over to the Irish Free State.

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State, Richmond Barracks is handed over to the Irish National Army and renamed Kehoe Barracks, after the late General Commandant, Tom Kehoe.

Kehoe had been a member of ‘The Squad’, the Irish Republican Army assassination team directed by Michael Collins who killed British intelligence officers (G Division), some of whom had processed the rebel prisoners in Richmond Barracks in 1916.

The Irish Free State is formed with the creation of a border separating six Northern counties from the rest of the island. This is agreed within the Anglo-Irish Treaty. A bitter civil war ensues between anti-Treaty and pro-Treaty forces; after eleven months it is won by the pro-Treaty side.

In his ‘Dublin of the Future’ proposal, town planner Patrick Abercrombie remarks that as several barracks ‘hang like a ring of forts’ around the city, they were ideal sites for parks and recreation. Dublin would then have a linked ring of playgrounds from which ‘small children’s playgrounds’ would be no further than a quarter of a mile as that ‘is as far as small children should be expected to go’.

(Dublin of the Future by Patrick Abercrombie, 1922)

Kehoe Barracks is vacated by the Irish Army and in October 1924 it is leased to Dublin Corporation for 98 years.

In the new Irish Free State, it is recognised that housing should be a priority and over the next 50 years, a mixture of homes are built on the site which becomes known as Keogh Square (sometimes spelt Kehoe).

Disused army barracks are considered to accommodate tenants and in the coming years, Kehoe Barracks, Marshelsea Barracks and Beggars Bush Barracks are converted into temporary flats for ‘the poorer class of workers’ (Report 1925)

Kehoe Barracks is handed over to Dublin Corporation to house ‘the poorer class of workers’ (Report 1925).

The barrack buildings are converted into 202 flats, 24 temporary dwellings and old military storage huts become cottages, known as ‘the huts’.

Click here to watch ‘Barrack Square Estate’ a film by Joe Lee.

The former garrison chapel used by soldiers becomes the Church of St Michael of the Angels to accommodate the growing numbers in the Parish and is officially opened by Archbishop Byrne.

The chancel windows are from the Harry Clarke School of stained glass and this one is attributed to William Dowling who trained under Clarke himself.

The Christian Brothers open St Michael’s school in the old recreation rooms and the gym - which still contains an original pommel exercise horse.

Hundreds of families live in Keogh Square up till the 1960s and they become known as ‘Barrackers’. They form a close-knit community with a strong sense of identity.

Local people still have fond memories of the early years in Keogh Square.

During the 1960s and 1970s, most of the barracks is demolished to make way for new public housing.

In 1967 Tyrone Place and Square, just outside the barracks, are cleared for flats to house 96 families. The new blocks can be seen on the left of the photograph, with the distinctive round tower stairwell. They are still standing today in 2023.

St Michael's Estate is built by Dublin City Council on the site to house working-class families and the elderly. The first residents recall spacious flats with heating coming through the floors. There is a playground and football pitch for children. The early years of the estate sees a connected and close-knit community of families and tenants, as described by Liam O’Meara;

‘The women…would stand at the kitchen windows and have a conversation between floors..and of course you could join in, if you wanted to’ (O’Meara in Joe Lee's film ‘Barrack Square Estate’).

During the 1980s the drug epidemic hit Dublin and decimates several working-class communities, St Michael’s Estate being one of many. Over time the estate changes in atmosphere and feels less safe. Various communities take action and participate in a ‘Concerned Parents Against Drugs’ campaign, a community city response to the issue of drugs.

A significant number of families use the opportunity of the new ‘Surrender Grant’ to move out and buy houses nearby. This brings more changes. St Michael’s begins to deteriorate as maintenance repairs become more infrequent.

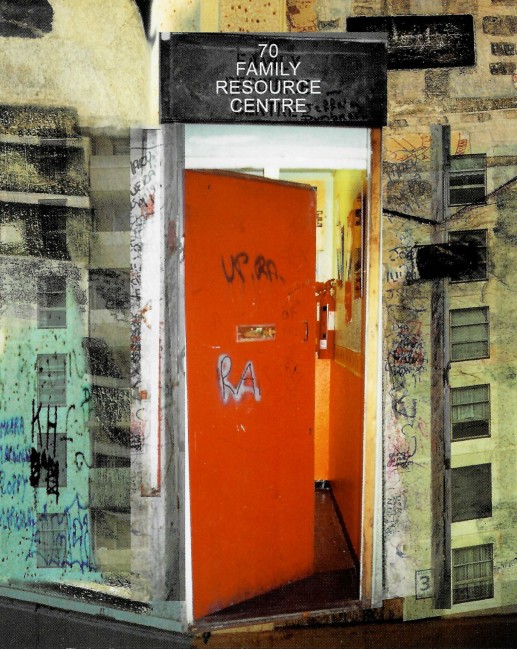

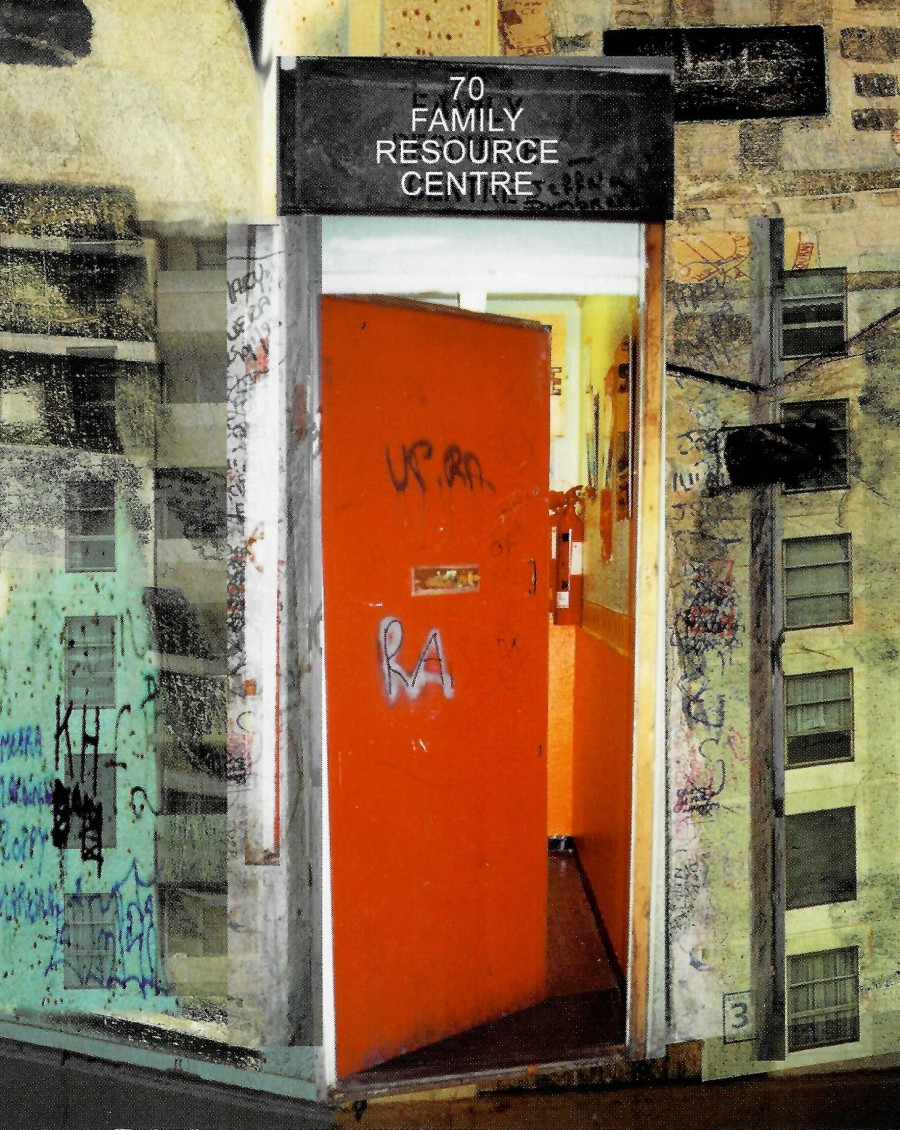

For the first time, lone parents are allocated affordable housing and young mothers become an active and significant group on the estate. With local women and Sister Jo Kennedy, they organise to set up a Family Resource Centre in No 70, a vacant flat, with child-minding facilities. No 70 is also used by the Women’s Programme, Tenants Group and the Youth Project with an open door policy.

38 years later the Family Resource Centre still plays an important role in the area today.

St Michael's Christian Brothers school closes.

The classrooms and the gym it occupies become vacant and fall into disrepair. The cupola in the gym and the veranda are removed by this time.

In May, the Inchicore Ledwidge Society, dedicated to preserving the memory and poetic legacy of Francis Ledwidge, 1887 - 1917, unveil a plaque dedicated to the poet.

The last block of St Michael's Estate is demolished and plans are developed to restore the gym and remaining rooms.

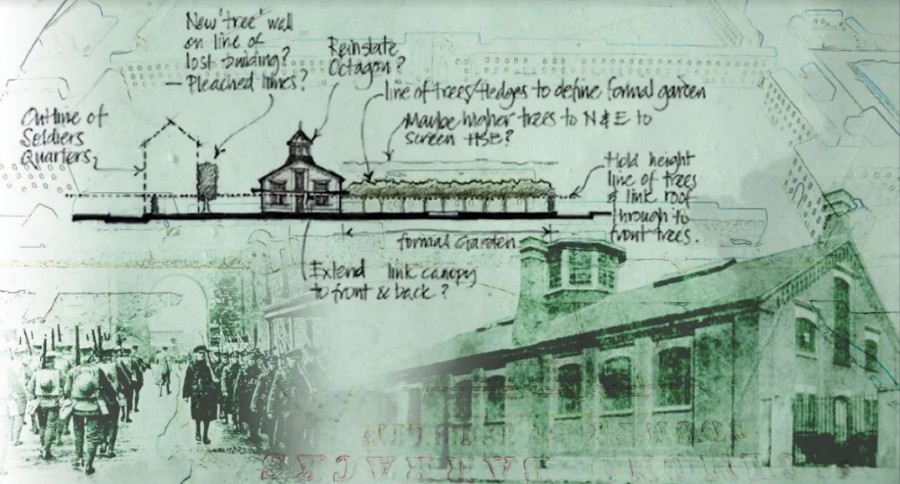

The Inchicore Kilmainham Heritage Group and the Richmond Barracks Advisory Committee work to restore the barracks with Dublin City Council.

Members of the Richmond Barracks Advisory Committee inspect the building restoration process.

The early barracks would have also covered the green area on the left of the gym.

The local community attends the launch of the Richmond Barracks renovations as Dublin City Council include it in the Decade of Centenaries to commemorate the Easter Rising of 1916.

Purcell Construction and Blackwood Associates architects are contracted to carry out the restoration works.

To mark the centenary of 1916, Richmond Barracks opens on May 2nd, 2016. Festivities include military bands, dramatic recreations and performances.

At the opening event people remember Keogh Square and St Michael’s estate.

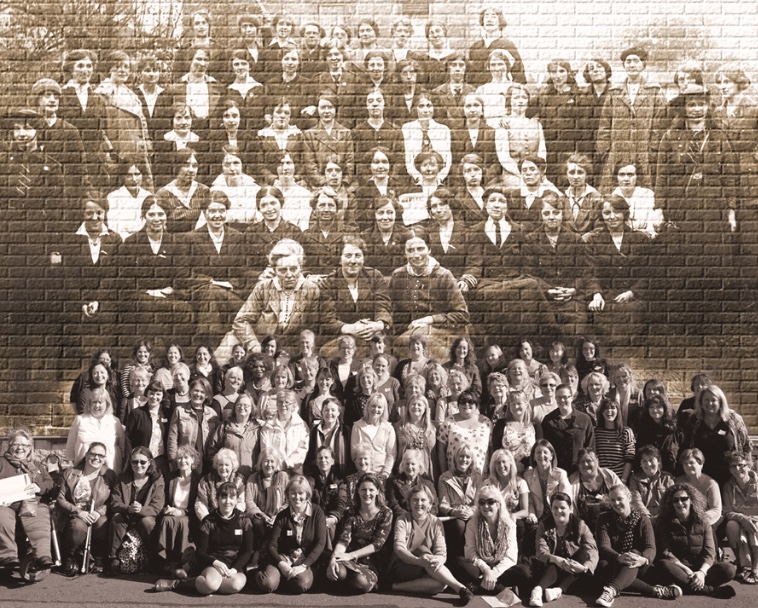

Women of the Yarn School sit below a photograph of the women and girls who took part in the Easter Rising of 1916.

The Yarn School was set up with a mission to ‘educate, inspire and entertain through the medium of textiles and this has been continued by the Liberties Weavers, in the Dublin 8 area.

The 77 Women Commemoration Quilt Project by the Yarn School is designed to create a conversation between the women of 1916 and women living in Ireland today.

A group of 77 women were invited to creatively respond to the stories of the 77 women imprisoned in Richmond Barracks.

Richmond Barracks becomes a cultural centre, home to Inchicore Library and a programme of cultural activities including cultural workshops and events, eco-gardening, historical tours and talks.

With thanks to:

The archives, museums and libraries who allowed use of images.

Inchicore Ledwidge Society.

Inchicore Kilmainham Heritage Group.

St Michael’s Family Resource Centre.

Donal Fallon.

Fergus Whelan.

Joe Lee.

Liam O’Meara.

Pat Garry.

Further reading from your local library:

Liam O'Meara, From Richmond Barracks to Keogh Square, (Dublin, 2014)

Liam O'Meara, Who remembers Keogh Square?, (Dublin, 2016)

Mary McAuliffe & Liz Gillis, We were there, 77 women of the Easter Rising, (Dublin, 2016)

Seosamh Ó Broin, Inchicore & Kilmainham & district, (Dublin, 1999)

Michael Conaghan (Ed), The Grand Canal: Inchicore & Kilmainham, (Dublin, 1994)

Gregg Ryan, The works celebrating 150 years of Inchicore works, (Dublin, 1996)